When the job at hand is measuring something with micron-range precision, thoughts generally turn to a tool with a Mitutoyo or Starrett nameplate. But with a clever design and a little electronics know-how, it turns out you can 3D print a displacement sensor for measuring in the micron range for only about $10.

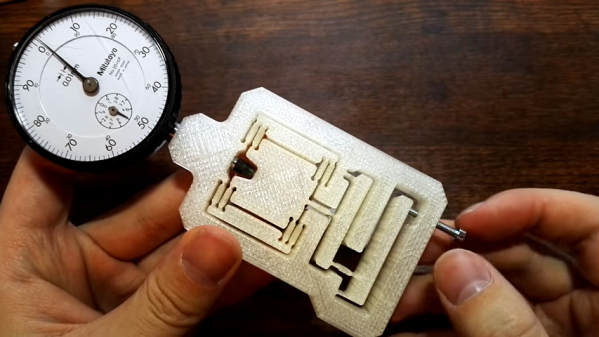

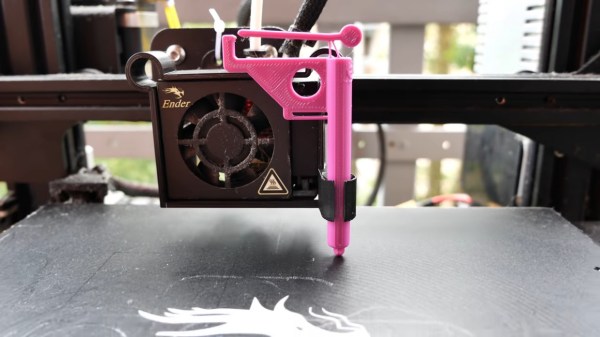

While the tool that [BubsBuilds] came up with isn’t as compact as a dial indicator and probably won’t win any industrial design awards, that doesn’t detract from its usefulness. And unlike a dial indicator — at least the analog type — this sensor outputs an easily digitized signal. That comes courtesy of a simple opto-interrupter sensor, which measures the position of a fine blade within its field of view. The blade is attached to a flexure that constrains its movement to a single plane; the other end of the flexure has a steel ball acting as a stylus. In use, any displacement of the stylus results in more or less light being received by the phototransistor in the opto-interrupter; the greater the deflection, the less light and the lower the current through the transistor. In addition to the sensor itself, [Bub] printed a calibration jig that allows precision gauge blocks or simple feeler gauges to be inserted in front of the stylus. The voltage across the emitter resistor for these known displacements is then used to create a calibration curve.

[Bub] says he’s getting 5-micron repeatability with careful calibration and multiple measurements of each gauge block, which seems pretty impressive to us. If you don’t need the digital output, this compliant mechanism dial indicator might be helpful too. Continue reading “Flexures Keep This Printed Displacement Sensor In Line”

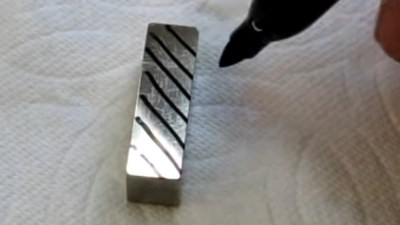

[Tom] from [oxtoolco] got his hands on a tool that measures in 1/10,000,000th (that’s one ten-millionth) increments and was wondering what kind of shenanigans you can do with this Lamborghini of dial indicators. It’s one thing to say you’re going to measure ink, but coming up with the method is the leap. In this case it’s a gauge block — a piece of precision ground metal with precise dimensions and perfectly perpendicular faces. By zeroing the indicator on the block, then adding lines from the Sharpie and measuring again, you can deduce the thickness of the ink markings.

[Tom] from [oxtoolco] got his hands on a tool that measures in 1/10,000,000th (that’s one ten-millionth) increments and was wondering what kind of shenanigans you can do with this Lamborghini of dial indicators. It’s one thing to say you’re going to measure ink, but coming up with the method is the leap. In this case it’s a gauge block — a piece of precision ground metal with precise dimensions and perfectly perpendicular faces. By zeroing the indicator on the block, then adding lines from the Sharpie and measuring again, you can deduce the thickness of the ink markings.