As Earthlings, most of us don’t spend a lot of extra time thinking about the gravity on our home planet. Instead, we go about our days only occasionally dropping things or tripping over furniture but largely attending to other matters of more consequence. When humans visit other worlds, though, there’s a lot more consideration of the gravity and its effects on how humans live and many different ways of training for going to places like the Moon or Mars. This gravity simulator, for example, lets anyone experience what it would be like to balance an object anywhere with different gravity from Earth’s.

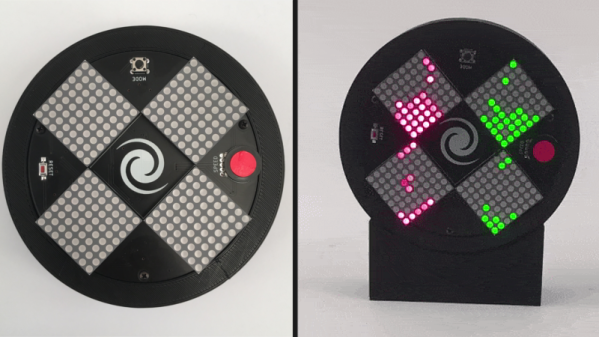

The simulator itself largely consists of a row of about 60 NeoPixels, spread out in a line along a length of lightweight PVC pipe. They’re controlled by an Arduino Nano which has a built-in inertial measurement unit, allowing it to sense the angle the pipe is being held at as well as making determinations about its movement. A set of LEDs on the NeoPixel strip is illuminated, which simulates a ball being balanced on this pipe, and motion one way or the other will allow the ball to travel back and forth along its length. With the Earth gravity setting this is fairly intuitive but when the gravity simulation is turned up for heavier planets or turned down for lighter ones the experience changes dramatically. Most of the video explains the math behind determining the effects of a rolling ball in each of these environments, which is worth taking a look at on its own.

While the device obviously can’t change the mass or the force of gravity by pressing a button, it’s a unique way to experience and feel what a small part of existence on another world might be like. With enough budget available there are certainly other ways of providing training for other amounts of gravity like parabolic flights or buoyancy tanks, although one of the other more affordable ways of doing this for laypeople is this low-gravity acrobatic device.

Continue reading “Experience Other Planets With The Gravity Simulator”