When it comes to hacking niches, breathing new life into vintage devices is always an exciting challenge. [t0mg]’s recent project exemplifies this with his 1978 Sony FX-300 ‘Jackal’ radio. He’d already upgraded the radio in 2021 and turned it into a feature-packed marvel, but there’s always room for improvement.

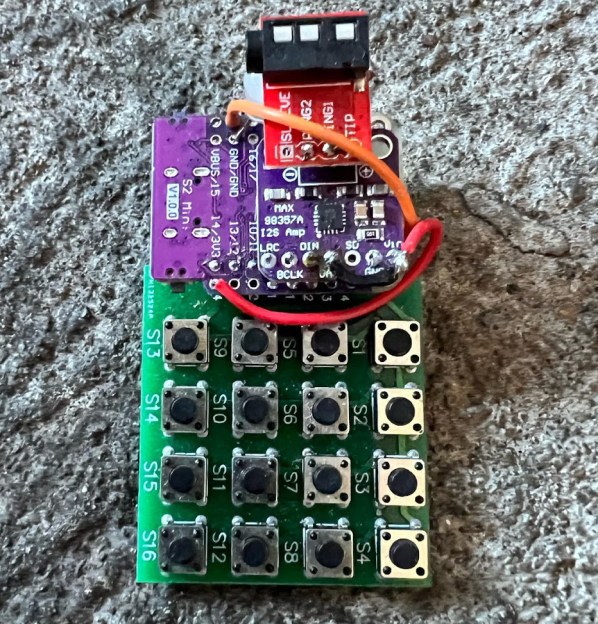

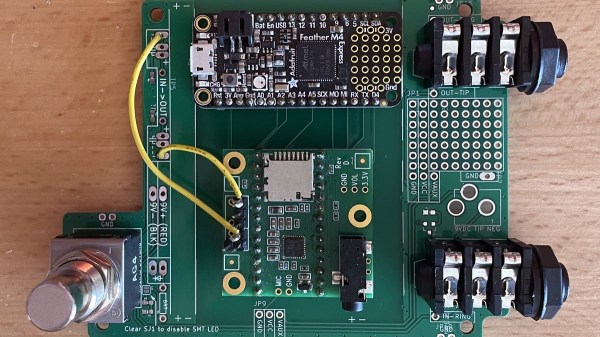

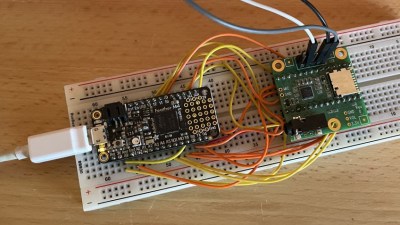

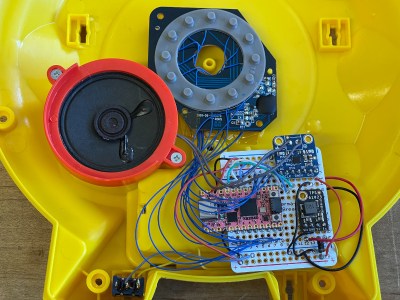

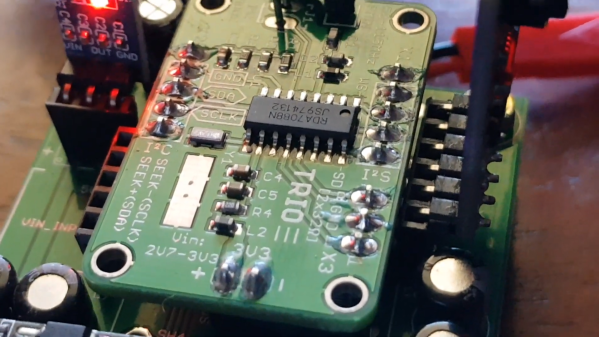

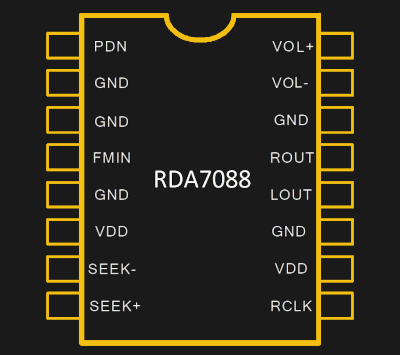

[t0mg]’s initial 2021 build had its quirks: noisy sound, a subpar display, and a non-functional radio module. Determined to enhance these aspects, he sourced an IPS version of the original 3.2″ ILI9431 LCD, significantly improving viewing angles. To tackle the audio issues, he integrated an M5Stack Atom microcontroller, utilizing its Bluetooth A2DP capabilities to deliver cleaner digital sound via I2S to the Teensy audio board. The Teensy itself got a complete wire overhaul just for the sake of good craftmanship.

The new setup also enabled the display of song metadata. Additionally, [t0mg] incorporated a dedicated Arduino Nano clone to manage inputs, streamlining the overall design. The revamped ‘Jackal’ now boasts a bunch of impressive features such as displaying RDS data for FM stations, voice recording, and an NFC reader for personalized playlists.

If you’re into radio makeovers, look into this post for a real golden oldie, or start out with the basics. For [t0mg]’s earlier improved version of this Jackal, read our article on it here.

Continue reading “Packing Even More Features Into A Classic Radio”