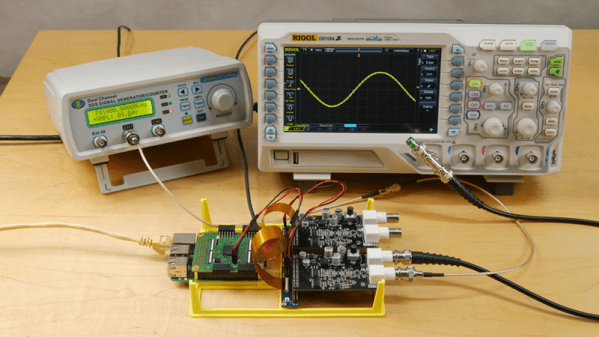

The Hackaday Superconference is over, which is a shame, but one of the great things about our conference is the people who manage to trek out to Pasadena every year to show us all the cool stuff they’re working on. One of those people was [Piotr Esden-Tempski], founder of 1 Bit Squared, and he brought some goodies that would soon be launched on a few crowdfunding platforms. The coolest of these was the iCEBreaker, an FPGA development kit that makes it easy to learn FPGAs with an Open Source toolchain.

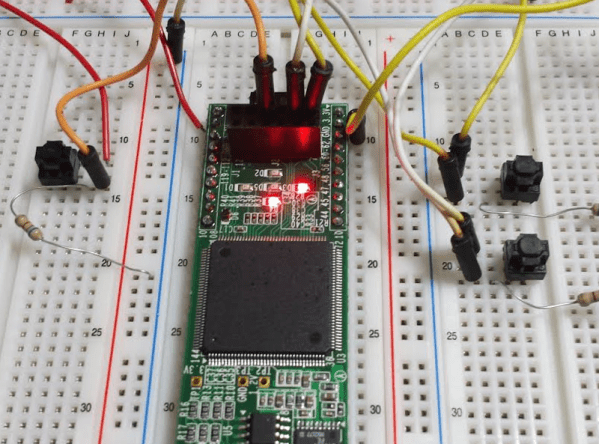

The hardware for the iCEBreaker includes the iCE40UP5K fpga with 5280 logic cells,, 120 kbit of dual-port RAM, 1 Mbit of single-port RAM, and a PLL, two SPIs and two I2Cs. Because the most interesting FPGA applications include sending bits out over pins really, really fast, there’s also 16 Megabytes of SPI Flash that allows you to stream video to a LED matrix. There are enough logic cells here to synthesize a CPU, too, and already the iCEBreaker can handle the PicoRV32, and some of the RISC-V cores. Extensibility is through PMOD connectors, and yes, there’s also an HDMI output for your vintage computing projects.

If you’re looking to get into FPGA development, there’s no better time. Joe Fitz‘s WTFpga workshop from the 2018 Hackaday Superconference has already been converted to this iCEBreaker board, and yes, the seven-segment display and DIP switches are available. Between this and the Open Source iCE toolchain, you’ve got a complete development system that’s ready to go, fun to play with, and extremely capable.