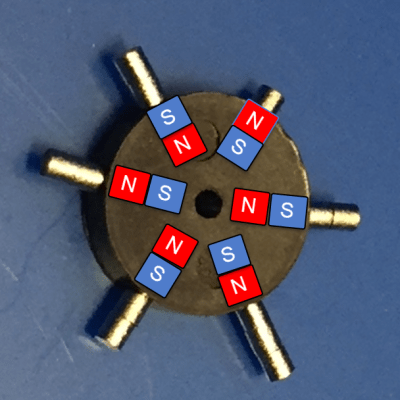

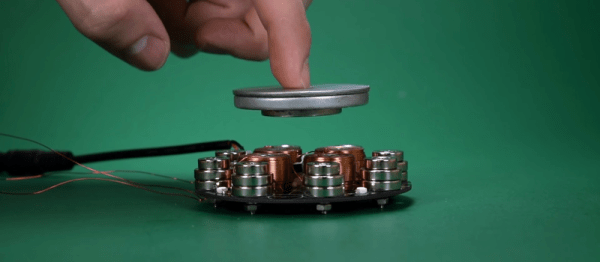

The folks at [K&J Magnetics] have access to precise magnetometers, a wealth of knowledge from years of experience but when it comes to playing around with a silly project like a magnetic koozie, they go right to trial and error rather than simulations and calculations. Granted, this is the opposite of mission-critical.

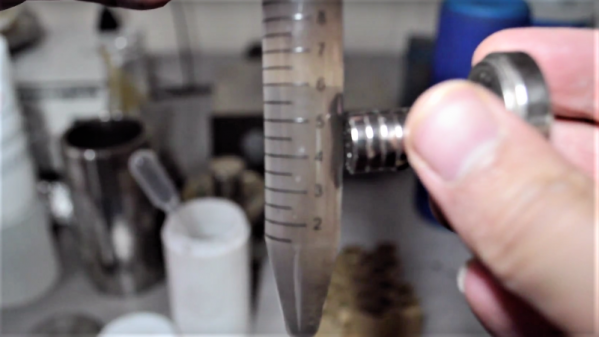

Once the experimentation was over, they got down to explaining their results so we can learn more than just how to hold our beer on the side of a toolbox. They describe three factors related to magnetic holding in clear terms that are the meat and bones of this experiment. The first is that anything which comes between the magnet and surface should be thin. The second factor is that it should be grippy, not slippy. The final element is to account for the leverage of the beverage being suspended. Say that three times fast.

Magnets are so cool for anything from helping visualize gas atoms, machinists’ tools, and circumventing firearm security features.