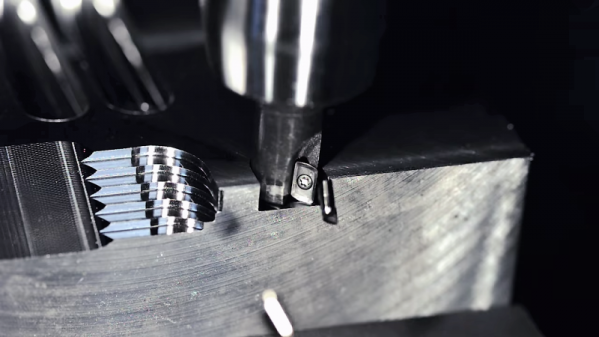

It seems a touch ironic that one of the main consumables in the machining industry is made out of one of the hardest, toughest substances there is. But such is the case for tungsten carbide inserts, the flecks of material that form the business end of most of the tools used to shape metal. And thanks to one of the biggest suppliers of inserts, Sweden’s Sandvik Coromant, we get this fascinating peek at how they’re manufactured.

For anyone into machining, the video below is a must see. For those not in the know, tungsten carbide inserts are the replaceable bits that form the cutting edges of almost every tool used to shape metal. The video shows how powdered tungsten carbide is mixed with other materials and pressed into complex shapes by a metal injection molding process, similar to the one used to make gears that we described recently. The inserts are then sintered in a furnace to bind the metal particles together into a cohesive, strong part. After exhaustive quality inspections, the inserts are ground to their final shape before being shipped. It’s fascinating stuff.

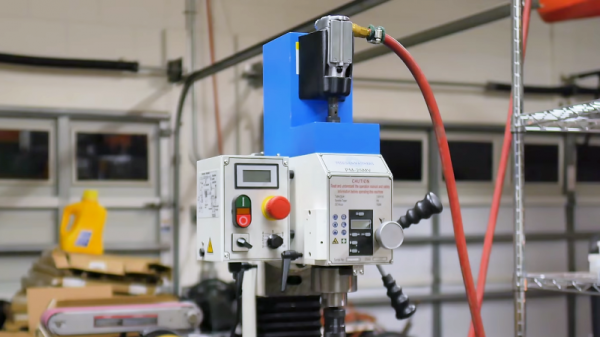

Coincidentally, [John] at NYC CNC just released his own video from his recent jealousy-inducing tour of the Sandvik factory. That video is also well worth watching, especially if you even have a passing interest in automation. The degree to which the plant is automated is staggering – from autonomous forklifts to massive CNC work cells that require no operators, this looks like the very picture of the factory of the future. It rolls some of the Sandvik video in, but the behind-the-scenes stuff is great.

Continue reading “The How And Why Of Tungsten Carbide Inserts, And A Factory Tour”

The full MatchSticks creation flow goes like this:

The full MatchSticks creation flow goes like this: