You’ve got a perfectly working software library to do just exactly what you want. Why aren’t you using it? Some of you are already yelling something about NIH syndrome or reinventing the wheel — I hear you. But at least sometimes, there’s a good enough reason to reinvent the wheel: let’s say you want to learn something.

Mike and I were talking about a cool hack on the podcast: a library that makes a floppy drive work with an Arduino, and even builds out a minimalistic DOS for it. The one thing that [David Hansel] didn’t do by himself was write the FAT library; he used the ever-popular FatFS by [Elm-ChaN]. Mike casually noted that he’s always wanted to write his own FAT library from scratch, just to learn how it works at the fundamental level, and I didn’t even bat an eyelash. Heck, if I had the time, I’d want to do that too!

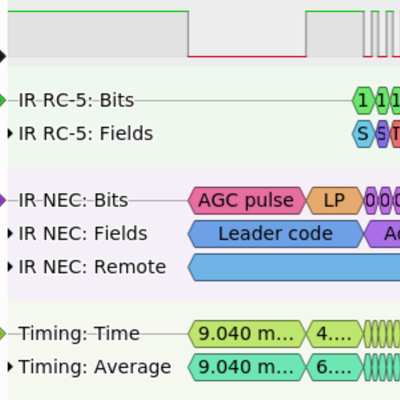

Look around on Hackaday, and you’ll see tons of hacks where people reinvent the wheel. In this superb soundbar hack, [Michal] spends a while working on the IR protocol by hand until succumbing to the call of IRMP, a library that has it all done for you. But if you read his writeup, he’s not sad; he learned something about IR protocols. This I2C paper tape reader is nothing if not a reinvention of the I2C wheel, but isn’t that the best way to learn?

Look around on Hackaday, and you’ll see tons of hacks where people reinvent the wheel. In this superb soundbar hack, [Michal] spends a while working on the IR protocol by hand until succumbing to the call of IRMP, a library that has it all done for you. But if you read his writeup, he’s not sad; he learned something about IR protocols. This I2C paper tape reader is nothing if not a reinvention of the I2C wheel, but isn’t that the best way to learn?

Yes it is. Think back to the last class you took. The teacher or professor certainly explained something to you in reasonable detail — that’s the job after all. And then you got some homework to do by yourself, and you did it, even though you were probably just going over the same stuff that the prof and countless others have gone through. But by doing it yourself, even though it was “reinventing the wheel”, you learned the material. And I’d wager that you wouldn’t have learned it without.

Of course, when the chips are down and the deadline is breathing hot down your neck, that might be the right time to just include that tried-and-true library. But if you really want to learn something yourself, you have every right to reinvent the wheel.