Back in the ’70s and ’80s, before we had computers that could do this sort of thing, there were fully analog video effects. These effects could posterize or invert the colors of a video signal, but for the best example of what these machines could do just go find some old music videos from Top of The Pops or Beat Club. Stuff gets weird, man. Unfortunately, all those analog broadcasting studios ended up in storage a few years ago, so if you want some sweet analog effects, you’re going to have to build your own. That’s exactly what [Julien]’s Video Mangler does. It rips up NTSC and PAL signals, does some weird crazy effects, and spits it right back out.

The inspiration for this build comes from an old ’80s magazine project called the ‘video palette’ that had a few circuits that blurred the image, turned everything negative, and could, if you were clever enough, become the basis for a chroma key. You can have a lot of fun when you split a video signal into its component parts, but for more lo-finess [Julien] is adding a microcontroller and a 12-bit DAC to generate signals that can be mixed in with the video signals. Yes, all of this can still be made now, even though analog TV died a decade ago.

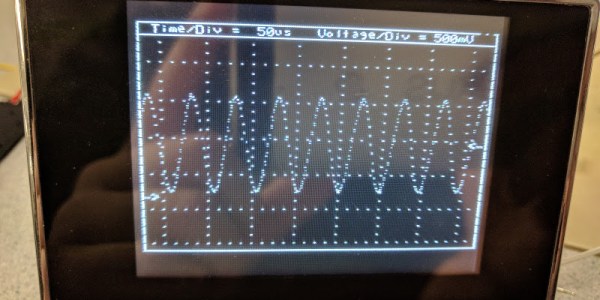

The current status of this project is a big ‘ol board with lots of obscure chips, and as with everything that can be described as circuit bending, there’s going to be a big panel with lots of dials and switches, probably stuffed into a laser-cut enclosure. There’s a mic input for blurring the TV with audio, and enough video effects to make any grizzled broadcast engineer happy.