For those that haven’t heard, ultrasonic levitation is a process by which two or more ultrasonic transducers are set opposite to each other and excited in such a way as to create a standing wave between them. The sound is, as the name implies, ultrasonic — so outside the range of human hearing — but strong enough so that the small, light objects can be positioned and held fixed in mid-air where there’s a pressure minimum in the standing wave. [Olimex] has created a small ultrasonic levitation kit that exemplifies this phenomena.

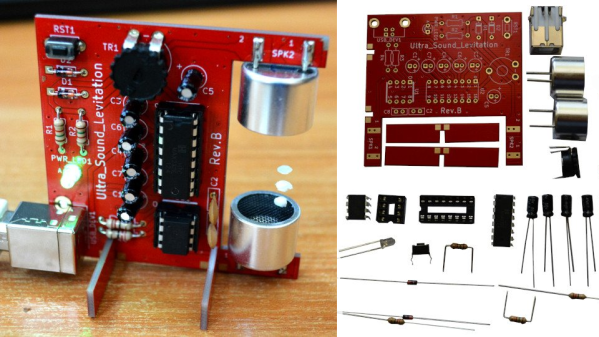

The kit itself is made using through-hole components, with an ATTiny85 as the core microcontroller to drive two TCT40-16T ultrasonic speakers, and a MAX232 to provide a USB interface drives the transducers (thanks to the folks in the comments for the correction). Two slotted rectangular PCB pieces that solder connect to the main board, provide a base so that the device stands upright when assembled. The whole device is powered through the USB connection, and the ultrasonic speakers output in the 40KHz range providing enough power to levitate small Styrofoam balls.

The project is, by design, an exercise in minimalism, providing a kit that can be easily assembled, and providing code that can be easily flashed onto the device, examined and modified. All the design files, including the bill of materials, KiCAD schematics, and source code are provided under an open source hardware license to allow for anyone wanting to know how such a project works, or to extend it themselves, ample opportunity. [Olimex] also has the kit for sale for those not wanting to source boards and parts themselves.

We’ve featured ultrasonic levitation devices before, from bare bones system driven by a NE555 to massive phased arrays.