Chances are pretty good that you have at least one digital image sensor somewhere close to you at this moment, likely within arm’s reach. The ubiquity of digital cameras is due to how cheap these sensors have become, and how easy they are to integrate into all sorts of devices. So why in the world would someone want to build an image sensor from discrete parts that’s 12,000 times worse than the average smartphone camera? Because, why not?

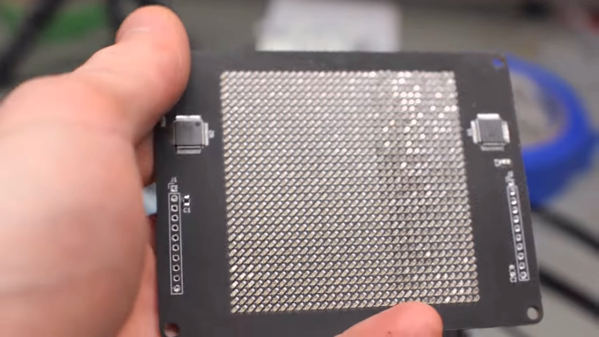

[Sean Hodgins] originally started this project as a digital pinhole camera, which is why it was called “digiObscura.” The idea was to build a 32×32 array of photosensors and focus light on it using only a pinhole, but that proved optically difficult as the small aperture greatly reduced the amount of light striking the array. The sensor, though, is where the interesting stuff is. [Sean] soldered 1,024 ALS-PT19 surface-mount phototransistors to the custom PCB along with two 32-bit analog multiplexers. The multiplexers are driven by a microcontroller to select each pixel in turn, one row and one column at a time. It takes a full five seconds to scan the array, so taking a picture hearkens back to the long exposures common in the early days of photography. And sure, it’s only a 1-kilopixel image, but it works.

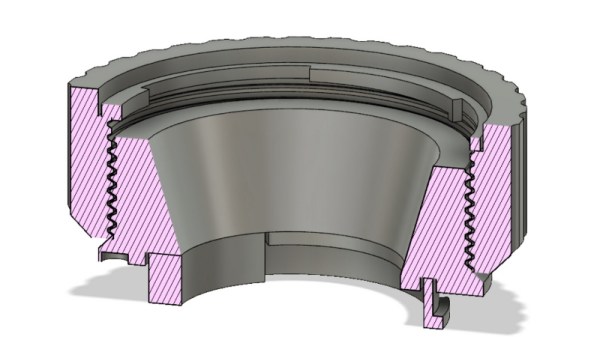

[Sean] has had this project cooking for a while – in fact, the multiplexers he used for the camera came up as a separate project back in 2018. We’re glad to see that he got the rest built, even with the recycled lens he used. One wonders how a 3D-printed lens would work in front of that sensor.

Continue reading “Image Sensor From Discrete Parts Delivers Glorious 1-Kilopixel Images”