You say you want to go to Mars, but the vanishingly thin atmosphere, the toxic and corrosive soil, the bitter cold, the deadly radiation that sleets down constantly, and the long, perilous journey that you probably won’t return from has turned you off a little. Fear not, because there’s still a way for you to get at least part of you to Mars: your intelligence. Curiosity, the Mars rover that’s on the eighth year of its 90-day mission, is completely remote-controlled, and NASA would like to add some self-driving capabilities to it. Which is why they’re asking for human help in classifying thousands of images of the Martian surface. By annotating images and pointing out what looks like soil and what looks like rock, you’ll be training an algorithm that one day might be sent up to the rover. If you’ve got the time, give it a shot — it seems a better use of time than training our eventual AI overlords.

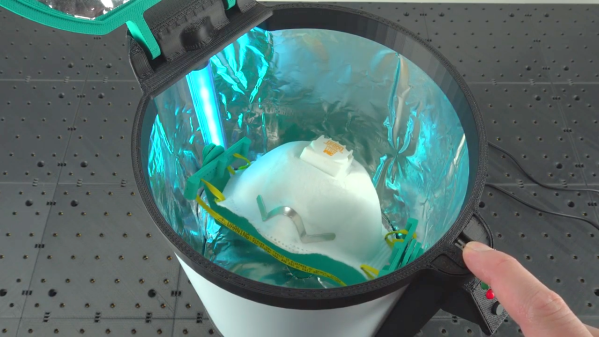

We got a tip this week that ASTM, the international standards organization, has made its collection of standards for testing PPE available to the public. With titles like “Standard Test Method for Resistance of Medical Face Masks to Penetration by Synthetic Blood (Horizontal Projection of Fixed Volume at a Known Velocity)”, it seems like the standards body wants to make sure that that homebrew PPE gets tested properly before being put into service. The timing of this release is fortuitous since this week’s Hack Chat features Hiram Gay and Lex Kravitz, colleagues from the Washington University School of Medicine who will talk about what they did to test a respirator made from a full-face snorkel mask.

There’s little doubt that Lego played a huge part in the development of many engineers, and many of us never really put them away for good. We still pull them out occasionally, for fun or even for work, especially the Technic parts, which make a great prototyping system. But what if you need a Technic piece that you don’t have, or one that never existed in the first place? Easy — design and print your own custom Technic pieces. Lego Part Designer is a web app that breaks Technic parts down into five possible blocks, and lets you combine them as you see fit. We doubt that most FDM printers can deal with the fine tolerances needed for that satisfying Lego fit, but good enough might be all you need to get a design working.

Chances are pretty good that you’ve participated in more than a few video conferencing sessions lately, and if you’re anything like us you’ve found the experience somewhat lacking. The standard UI, with everyone in the conference organized in orderly rows and columns, reminds us of either a police line-up or the opening of The Brady Bunch, neither of which is particularly appealing. The paradigm could use a little rethinking, which is what Laptops in Space aims to do. By putting each participant’s video feed in a virtual laptop and letting them float in space, you’re supposed to have a more organic meeting experience. There’s a tweet with a short clip, or you can try it yourself. We’re not sure how we feel about it yet, but we’re glad someone is at least trying something new in this space.

And finally, if you’re in need of a primer on charlieplexing, or perhaps just need to brush up on the topic, [pileofstuff] has just released a video that might be just what you need. He explains the tri-state logic LED multiplexing method in detail, and even goes into some alternate uses, like using optocouplers to drive higher loads. We like his style — informal, but with a good level of detail that serves as a jumping-off point for further exploration.