Any statement regarding the potential benefits and/or hazards of AI tends to be automatically very divisive and controversial as the world tries to figure out what the technology means to them, and how to make the most money off it in the process. Either meaning Artificial Inference or Artificial Intelligence depending on who you ask, AI has seen itself used mostly as a way to ‘assist’ people. Whether in the form of a chat client to answer casual questions, or to generate articles, images and code, its proponents claim that it’ll make workers more efficient and remove tedium.

In a recent paper published by researchers at Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) the findings from a survey are however that the effect is mostly negative. The general conclusion is that by forcing people to rely on external tools for basic tasks, they become less capable and prepared of doing such things themselves, should the need arise. A related example is provided by Emanuel Maiberg in his commentary on this study when he notes how simple things like memorizing phone numbers and routes within a city are deemed irrelevant, but what if you end up without a working smartphone?

Does so-called generative AI (GAI) turn workers into monkeys who mindlessly regurgitate whatever falls out of the Magic Machine, or is there true potential for removing tedium and increasing productivity?

Continue reading “Why AI Usage May Degrade Human Cognition And Blunt Critical Thinking Skills”

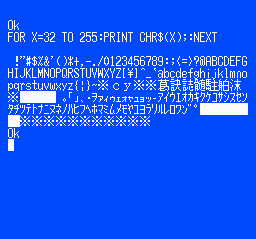

removable cartridge, complete with a BASIC interpreter and a collection of graphical editor tools for game creation.

removable cartridge, complete with a BASIC interpreter and a collection of graphical editor tools for game creation. even a map editor. We think inputting BASIC code via a gamepad would get old fast, but it would work a little better for graphical editing.

even a map editor. We think inputting BASIC code via a gamepad would get old fast, but it would work a little better for graphical editing.