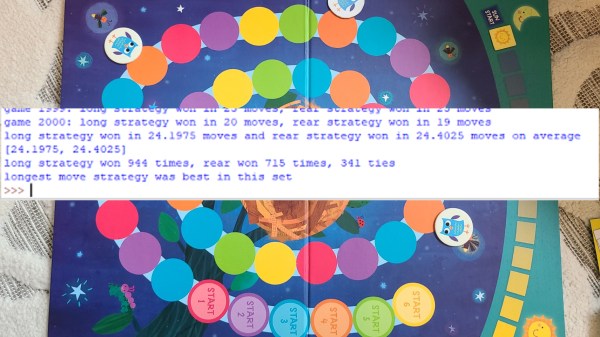

Simulating a tabletop game can be done for several reasons: to play the game digitally, to create computer opponent(s), or to prove someone wrong. In [Everett]’s case, he used Python to prove which adult was right about basic strategy in a children’s game.

[Everett]’s 5-year-old loves a simple game called Hoot Owl Hoot! in which players cooperatively work to move owls along a track to the safety of a nest. Player pieces move on spaces according to the matching colors drawn from a deck of cards. If a space is already occupied, a piece may jump ahead to the next available spot. The game has a bit more to it than that, but those are the important parts. After a few games, the adults in the room found themselves disagreeing about which strategy was optimal in this simple game.

It seemed to [Everett] that it was best to move pieces in the rear, keeping player pieces grouped together and maximizing the chance of free moves gained by jumping over occupied spaces. [Everett]’s wife countered that a “longest move” strategy was best, and one should always select whichever piece would benefit the most (i.e. move the furthest distance) from any given move. Which approach wins games in the fewest moves? This small Python script simulates the game enough to iteratively determine that the two strategies are quite close in results, but the “longest move” strategy does ultimately come out on top.

As far as simulations go, it’s no Tamagotchi Singularity and [Everett] admits that the simulation isn’t a completely accurate one. But since its only purpose is to compare whether “no stragglers” or “longest move” wins in fewer moves, shortcuts like using random color generation in place of drawing the colors from a deck shouldn’t make a big difference. Or would it? Regardless, we can agree that board games can be fitting metaphors for the human condition.