Pretty much every modern car has some driver assistance feature, such as lane departure and blind-spot warnings, or adaptive cruise control. They’re all pretty cool, and they all depend on the car knowing where it is in space relative to other vehicles, obstacles, and even pedestrians. And they all have another thing in common: tiny radar sensors sprinkled around the car. But how in the world do they work?

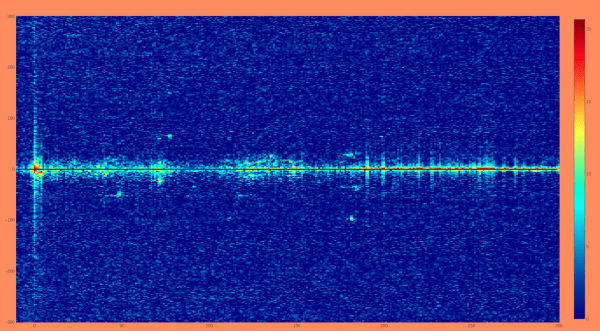

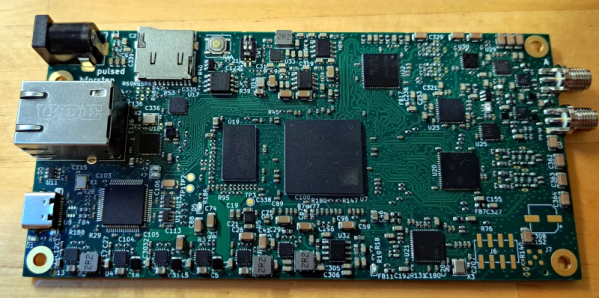

If you’ve pondered that question, perhaps after nearly avoiding rear-ending another car, you’ll want to check out [Marshall Bruner]’s excellent series on the fundamentals of FMCW radar. The linked videos below are the first two installments. The first covers the basic concepts of frequency-modulated continuous wave systems, including the advantages they offer over pulsed radar systems. These advantages make them a great choice for compact sensors for the often chaotic automotive environment, as well as tasks like presence sensing and factory automation. The take-home for us was the steep penalty in terms of average output power on traditional pulsed radar systems thanks to the brief time the radar is transmitting. FMCW radars, which transmit and receive simultaneously, don’t suffer from this problem and can therefore be much more compact.

Continue reading “Fundamentals Of FMCW Radar Help You Understand Your Car’s Point Of View”