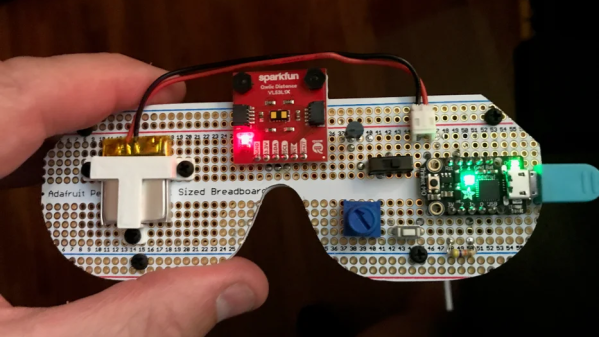

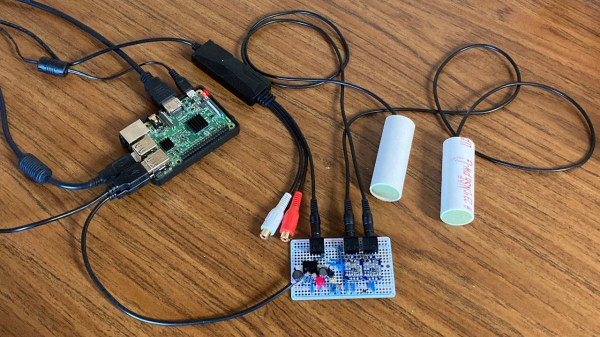

[tpsully]’s Radar Glasses are designed as a way of sensing the world without the benefits of normal vision. They consist of a distance sensor on the front and a vibration motor mounted to the bridge for haptic feedback. The little motor vibrates in proportion to the sensor’s readings, providing hands-free and intuitive feedback to the wearer. Inspired in part by his own experiences with temporary blindness, [tpsully] prototyped the glasses from an accessibility perspective.

The sensor is a VL53L1X time-of-flight sensor, a LiDAR sensor that measures distances with the help of pulsed laser light. The glasses do not actually use RADAR (which is radio-based), but the operation is in a sense quite similar.

The VL53L1X has a maximum range of up to 4 meters (roughly 13 feet) in a relatively narrow field of view. A user therefore scans their surroundings by sweeping their head across a desired area, feeling the vibration intensity change in response, and allowing them to build up a sort of mental depth map of the immediate area. This physical scanning resembles RADAR antenna sweeps, and serves essentially the same purpose.

There are some other projects with similar ideas, such as the wrist-mounted digital white cane and the hip-mounted Walk-Bot which integrates multiple angles of sensing, but something about the glasses form factor seems attractively intuitive.

Thanks to [Daniel] for the tip, and remember that if you have something you’d like to let us know about, the tips line is where you can do that.