“You should have used a 555” has become a bit of a meme around these parts lately, and for good reason. There seems to be little that these ubiquitous chips can’t be used for, and in a world where code often substitutes for hardware, it’s easy to point to instances where one could have just used a simple timer chip instead.

Definitely not in the meme category, though, is this overkill vacuum tube 555 timer. It comes to us via [David Lovett], aka [Usagi Electric], who has lately caught the “hollow state” electronics bug and has been experimenting with all sorts of vacuum tube recreations of circuits we’re far more used to seeing rendered in silicon than glass. The urge to replicate the venerable 555 in nothing but vacuum tubes is understandable, as it uses little more than a pair of comparators and a flip-flop, circuits [David] has already built vacuum tube versions of. The only part left was the discharge transistor; a pentode was enlisted to stand in for that vital function, making the circuit complete.

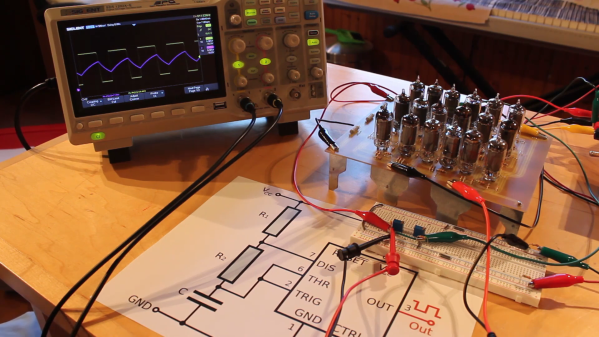

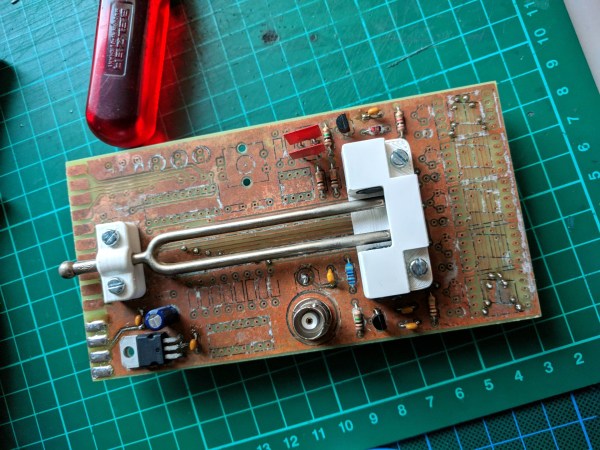

To physically implement the design, [David] built a large PCB to hold the 18 vacuum tubes and the handful of resistors and capacitors needed. Mounted on eight outsized leads made from sheet steel, the circuit pays homage to the original 8-pin DIP form of the 555. The video below shows the design and build process as well as testing of all the common modes of operation for the timer chip.

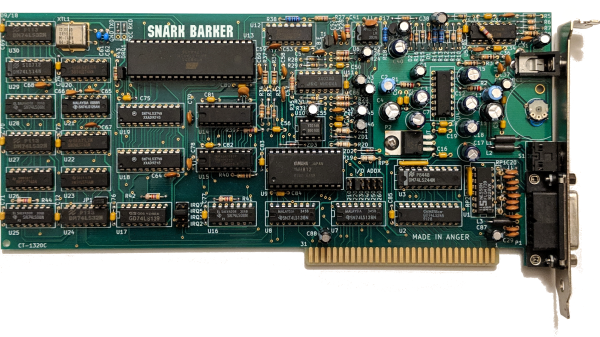

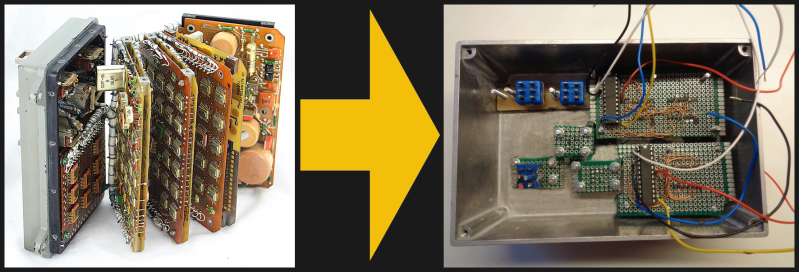

You can check out more of our coverage of [David]’s vacuum tube adventures, which started with his reverse-engineering of an old IBM logic module. And while he did a great job explaining the inner workings of the 555, you might want to take a deeper dive into how the venerable chip came to be.