[Ryan Schenk] had a problem: he built the perfect surfboard. Normally that wouldn’t present a problem, but in this case, it did because [Ryan] had no idea how he carved the gentle curves on the bottom of the board. So he built this homebrew 2D-scanner to make the job of replicating his hand-carved board a bit easier.

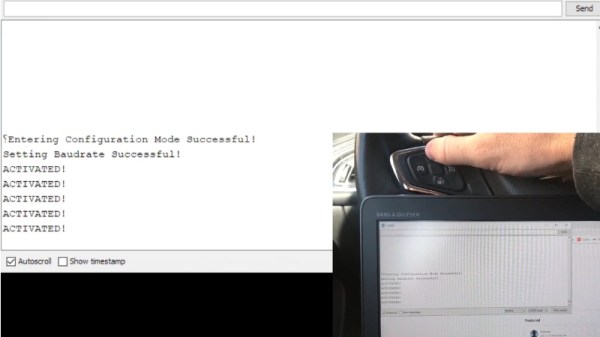

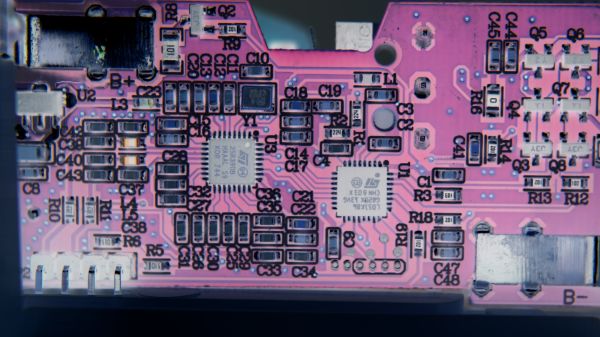

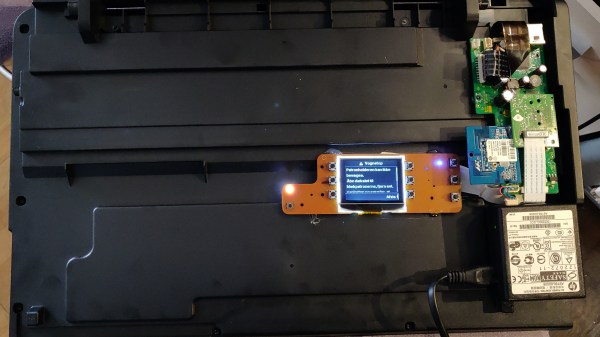

Dubbed the Scanbot 69420 – interpretation of the number is left as an exercise for the reader, my dude – the scanner is pretty simple. It’s just an old mouse carrying a digital dial indicator from Harbor Freight. The mouse was gutted, with even the original ball replaced by an RC plane wheel. The optical encoder and buttons were hooked to an Arduino, as was the serial output of the dial indicator. The Arduino consolidates the data from both sensors and sends a stream of X- and Z-axis coordinates up the USB cable as the rig slides across the board on a straightedge. On the PC side, a Node.js program turns the raw data into a vector drawing that represents the profile of the board at that point. Curves are captured at various points along the length of the board, resulting in a series of curves that can be used to replicate the board.

Yes, this could have been done with a straightedge, a ruler, and a pencil and paper – or perhaps with a hacked set of calipers – but that wouldn’t be nearly as much fun. And we can certainly see applications for this far beyond the surfboard shop.