In the days of carburetors and leaf spring suspensions, odometer fraud was pretty simple to do just by disconnecting the cable or even winding the odometer backwards. With the OBD standard and the prevalence of electronics in cars, promises were made by marketing teams that this risk had all but been eliminated. In reality, however, the manipulation of CAN bus makes odometer fraud just as easy, and [Andras] is here to show us exactly how easy with a teardown of a few cheap CAN bus adapters.

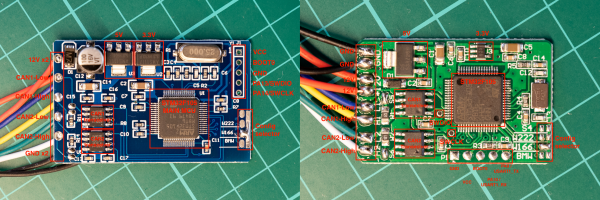

We featured another project that was a hardware teardown of one of these devices, but [Andras] takes this a step further by probing into the code running on the microcontroller. One would imagine that basic measures would have been taken by the attackers to obscure code or at least disable debugging modes, but on this one no such effort was made. [Andras] was able to dump the firmware from both of his test devices and start analyzing them.

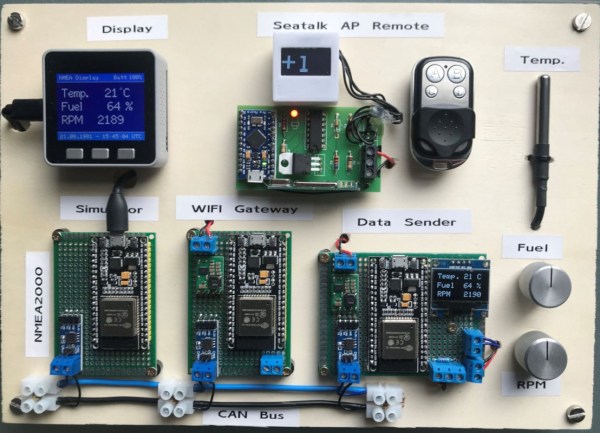

Analyzing the codes showed identical firmware running on both devices, which made his job half as hard. It looked like the code was executing a type of man-in-the-middle attack on the CAN bus which allowed it to insert the bogus mileage reading. There’s a lot of interesting information in [Andras]’s writeup though, so if you’re interested in CAN bus or attacks like this, it’s definitely worth a read.