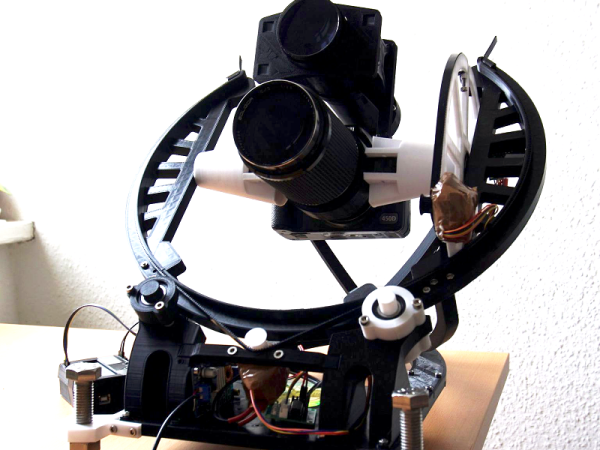

What does one do when frustrated at the lack of affordable, open source portable trackers? If you’re [OG-star-tech], you design your own and give it modular features that rival commercial offerings while you’re at it.

![]() What’s a star tracker? It’s a method of determining position based on visible stars, but when it comes to astrophotography the term refers to a sort of hardware-assisted camera holder that helps one capture stable long-exposure images. This is done by moving the camera in such a way as to cancel out the effects of the Earth’s rotation. The result is long-exposure photographs without the stars smearing themselves across the image.

What’s a star tracker? It’s a method of determining position based on visible stars, but when it comes to astrophotography the term refers to a sort of hardware-assisted camera holder that helps one capture stable long-exposure images. This is done by moving the camera in such a way as to cancel out the effects of the Earth’s rotation. The result is long-exposure photographs without the stars smearing themselves across the image.

Interested? Learn more about the design by casting an eye over the bill of materials at the GitHub repository, browsing the 3D-printable parts, and maybe check out the assembly guide. If you like what you see, [OG-star-tech] says you should be able to build your own very affordably if you don’t mind 3D printing parts in ASA or ABS. Prefer to buy a kit or an assembled unit? [OG-star-tech] offers them for sale.

Frustration with commercial offerings (or lack thereof) is a powerful motive to design something or contribute to an existing project, and if it leads to more people enjoying taking photos of the night sky and all the wonderful things in it, so much the better.