Here’s a neat trick for your next 3D-printer build or retrofit: a Z-axis sensor using a DIY strain gauge made from SMD resistors. We’re betting it could have plenty of other applications, too.

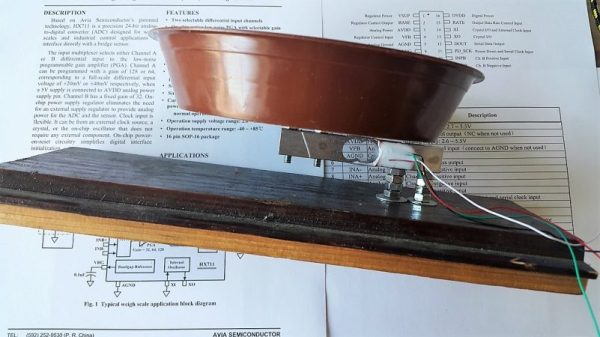

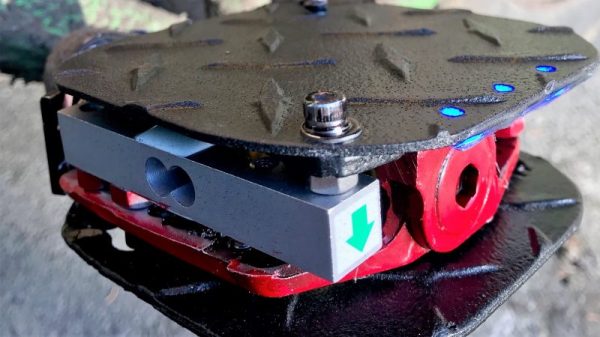

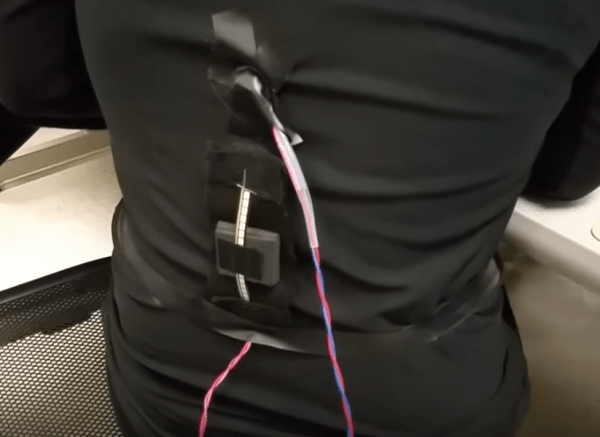

Conventional load cells, at least the ones you can pick up cheaply from the usual sources or harvest from old kitchen or bathroom scales, are usually way too big to be used on the extruder of a 3D-printer. [IvDm] wanted to build a touch sensor for his Hybercube printer, so he built his own load cell to do it. It consists of four 1000 ohm SMD resistors in the big 2512 device size. He mounted them to an X-shaped PCB and wired them in the classic Wheatstone bridge configuration, with two resistors on one side of the board and two on the other.

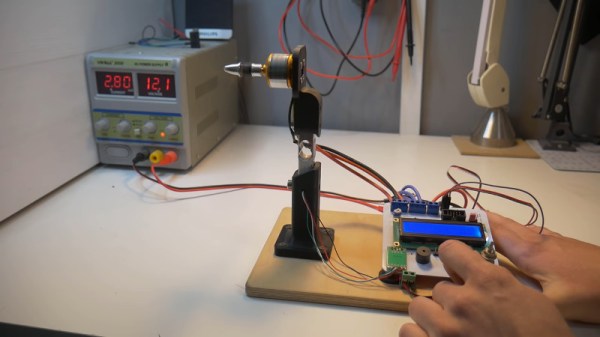

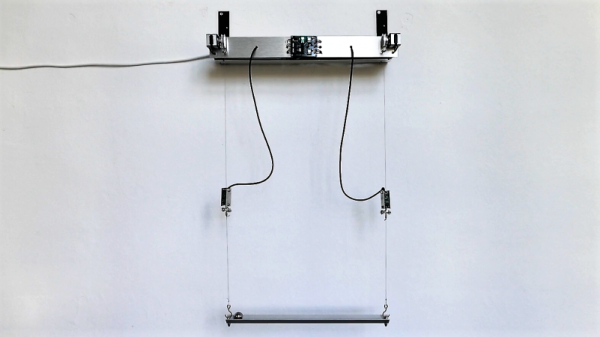

The extruder mounts into a hole in the center of the board and floats on it. Through an HX711 load cell driver chip, the bridge senses the slight flex of the board when the extruder bottoms out on the bed, and an ATtiny85 pulls a limit switch input to ground. [IvDm] even did some repeatability testing with this sensor and it turned out to be surprisingly consistent. The first minute or so of the video below shows it in action on the Hypercube.

We found the use of SMD resistors as strain gauges pretty clever here, but there’s plenty to do with off-the-shelf load cells: measuring how much filament is left on a roll, checking the thrust of a model rocket engine, or even figuring out if you’re peeing correctly.

Continue reading “Quartet Of SMD Resistors Used To Sense Z-Axis Height”