Buried on page 25 of the 2019 budget proposal for the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), under the heading “Fundamental Measurement, Quantum Science, and Measurement Dissemination”, there’s a short entry that has caused plenty of debate and even a fair deal of anger among those in the amateur radio scene:

NIST will discontinue the dissemination of the U.S. time and frequency via the NIST radio stations in Hawaii and Ft. Collins, CO. These radio stations transmit signals that are used to synchronize consumer electronic products like wall clocks, clock radios, and wristwatches, and may be used in other applications like appliances, cameras, and irrigation controllers.

The NIST stations in Hawaii and Colorado are the home of WWV, WWVH, and WWVB. The oldest of these stations, WWV, has been broadcasting in some form or another since 1920; making it the longest continually operating radio station in the United States. Yet in order to save approximately $6.3 million, these time and frequency standard stations are potentially on the chopping block.

What does that mean for those who don’t live and breathe radio? The loss of WWV and WWVH is probably a non-event for anyone outside of the amateur radio world. In fact, most people probably don’t know they even exist. Today they’re primarily used as frequency standards for calibration purposes, but in recent years have been largely supplanted by low-cost oscillators.

What does that mean for those who don’t live and breathe radio? The loss of WWV and WWVH is probably a non-event for anyone outside of the amateur radio world. In fact, most people probably don’t know they even exist. Today they’re primarily used as frequency standards for calibration purposes, but in recent years have been largely supplanted by low-cost oscillators.

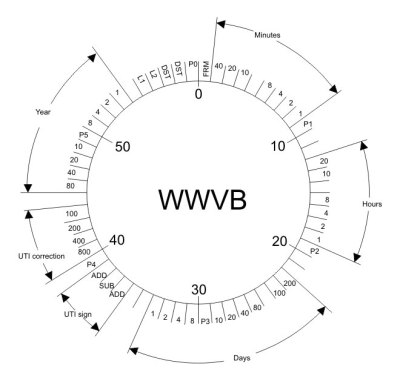

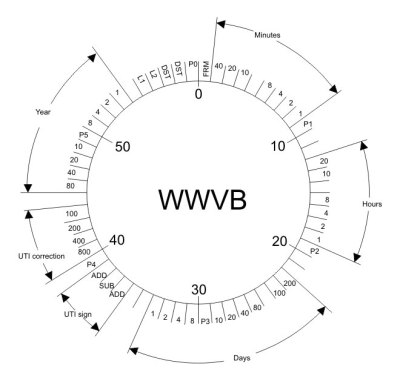

But WWVB on the other hand is used by millions of Americans every day. By NIST’s own estimates, over 50 million timepieces of some form or another automatically synchronize their time using the digital signal that’s been broadcast since 1963. Therein lies the debate: many simply don’t believe that NIST is going to shut down a service that’s still actively being used by so many average Americans.

The problem lies with the ambiguity of the statement. That the older and largely obsolete stations will be shuttered is really no surprise, but because the NIST budget doesn’t specifically state whether or not the more modern WWVB is also included, there’s room for interpretation. Especially since WWVB and WWV are both broadcast from Ft. Collins, Colorado.

What say the good readers of Hackaday? Do you think NIST is going to take down the relatively popular WWVB? Are you still using devices that sync to WWVB, or have they all moved over to pulling their time down over the Internet? If WWVB does go off the air, are you prepared to setup your own pirate time station?

[Thanks to AG6QR for the tip.]

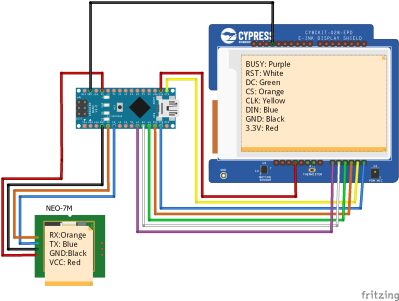

If you mention a clock that receives its time via radio, most people will think of one taking a long wave signal from a station such as WWVB, MSF, or DCF77. A more recent trend however has been for clocks that set themselves from orbiting navigation satellites, and an example comes to us from [KK99]. It’s a relatively simple hardware build in that it is simply an Arduino Nano, GPS module, and e-ink display module wired together, but it provides an interesting exercise in running through the code required for a GPS clock.

If you mention a clock that receives its time via radio, most people will think of one taking a long wave signal from a station such as WWVB, MSF, or DCF77. A more recent trend however has been for clocks that set themselves from orbiting navigation satellites, and an example comes to us from [KK99]. It’s a relatively simple hardware build in that it is simply an Arduino Nano, GPS module, and e-ink display module wired together, but it provides an interesting exercise in running through the code required for a GPS clock.