When you saw the picture for this article, did you think of a peacock’s feather? These fibers are not harvested from birds, and in fact, the colors come from transparent rubber. As with peacock feathers, they come from the way light reflects off layers of differing materials, this is known as optical interference, and it is the same effect seen on oil slicks. The benefit to using transparent rubber is that the final product is flexible and when drawn, the interference shifts. In short, they change color when stretched.

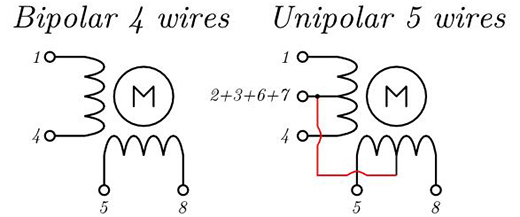

Most of the sensors we see and feature are electromechanical, which has the drawback that we cannot read them without some form of interface. Something like a microcontroller, gauge, or a slew of 555 timers. Reading a single strain gauge on a torque wrench is not too tricky, but simultaneously reading a dozen gauges spread across a more complex machine such as a quadcopter will probably require graphing software to generate a heat map. With this innovation it could now be done with an on-board camera in real-time. Couple that with machine learning and perhaps you could launch Skynet. Or build a better copter.

The current proof-of-concept weaves the fibers into next-generation bandages to give an intuitive sense of how tightly a dressing should be applied. For the average first-aid responder, the rule is being able to slide a finger between the fabric and skin. That’s an easy indicator, but it only works after the fact whereas saying that the dressing should be orange while wrapping gives constant feedback.