Anyone who was lucky enough to secure a Gmail invite back in early 2004 would have gasped in wonder at the storage on offer, a whole gigabyte! Nearly two decades later there’s more storage to be had for free from Google and its competitors, but it’s still relatively easy to hit the paid tier. Consider this though, how about YouTube as an infinite cloud storage medium?

The proof of concept code from [] works by encoding binary files into video files which can then be uploaded to the video sharing service. It’s hardly a new idea as there were clever boxes back in the 16-bit era that would do the same with a VHS video recorder, but it seems that for the moment it does what it says, and turns YouTube into an infinite cloud file store.

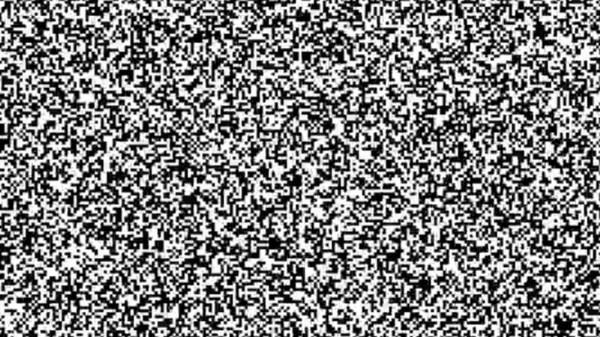

The README goes into a bit of detail about how the code tries to avoid the effects of YouTube’s compression algorithm. It eschews RGB colour for black and white pixels, and each displayed pixel in the video is made of a block of the real pixels. The final video comes in at around four times the size of the original file, and looks like noise on the screen. There’s an example video, which we’ve placed below the break.

Whether this is against YouTube’s TOS is probably open for interpretation, but we’re guessing that the video site could spot these uploads with relative ease and apply a stronger compression algorithm which would corrupt them. As an alternate approach, we recommend hiding all your important data in podcast episodes.