I’ve been told all my life about old-timey Army/Navy surplus stores where you could buy buckets of FT-243 crystals, radio gear, gas masks, and even a Jeep boxed-up in a big wooden crate. Sadly this is no longer the case. Today surplus stores only have contemporary Chinese-made boots, camping gear, and flashlights. They are bitterly disappointing except for one surplus store that I found while on vacation in the Adirondacks: Patriot of Lake George.

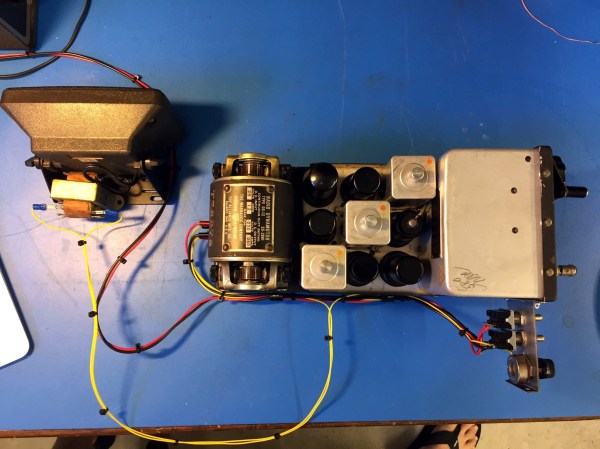

There I found a unicorn of historical significance; an un-modified-since-WW2 surplus CBY-46104 receiver with dynamotor. The date of manufacture was early-war, February 1942. This thing was preserved as good as the day it was removed from its F4F Hellcat. No ham has ever laid a soldering iron or a drill bit to it. Could this unit have seen some action in the south Pacific? Imagine the stories it could tell!

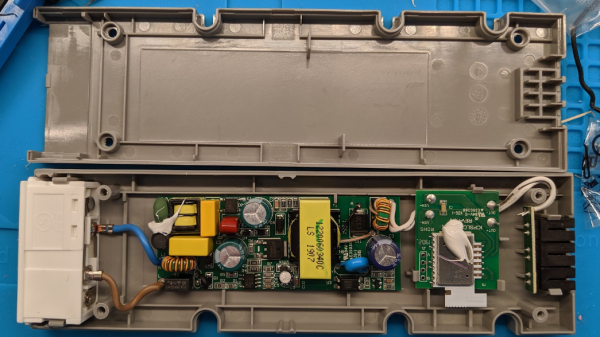

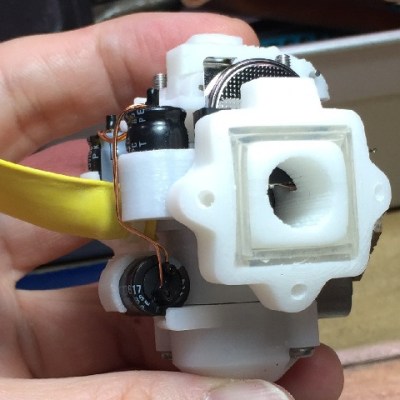

My unconventional restoration of this radio followed strict rules so as to minimize the evidence of repair both inside and out yet make this radio perform again as though it came fresh off the assembly line. Let’s see how I did.

Continue reading “WWII Aircraft Radio Roars To Life: What It Takes To Restore A Piece Of History”