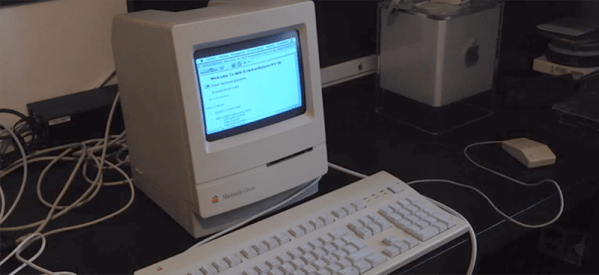

While it may not be the case anymore, if you compare a Mac and a PC from 1990, the Mac comes out far ahead. PCs suffered with DOS, while the Mac enjoyed real, non-bitmapped fonts. Where a Windows PC required LANMAN to connect to a network, the Mac had networking built right into every single machine. In fact, any Mac from The Old Days can use this built-in networking to connect to the Internet, but most old Mac networking hacks have relied on PPP or other network to serial conversion. [Pierre] thought there was an incomplete understanding in getting old Macs up on the Internet and decided to connect a Mac Classic to the Internet with Apple’s built-in networking.

Since the very first Macintosh, Apple included a simple networking protocol that allowed users to share hard drives, folders, and printers over a local network. This networking setup was called LocalTalk. It wasn’t meant for internets or very large networks; the connection between computers was basically daisy chained serial cables and later RJ-11 (telephone) cables.

LocalTalk stuck around for a long time, and even now if you need to do anything with a Mac made in the last century, it’s your best bet for file transfer. Because of LocalTalk’s longevity, routers and LocalTalk to Ethernet adapters can be found fairly easily. The only problem is finding a modern device that speaks both TCP/IP and LocalTalk. You can’t use a new Mac for this; LocalTalk has been gone from OS X since Snow Leopard. You can do it with a Raspberry Pi, though.

With a little bit of futzing about with MacTCP and a few other pieces of software from 1993 or thereabouts, [Pierre] can even get his old Mac Classic online. Of course the browsers are all horribly outdated (making the Hackaday retro edition very useful), but [Pierre] was able to load up rotten.com. It takes a while with an 8MHz CPU and 4MB of RAM, but it does get the job done.

You can check out [Pierre]’s demo video below.

Continue reading “Better Networking With A Macintosh Classic” →

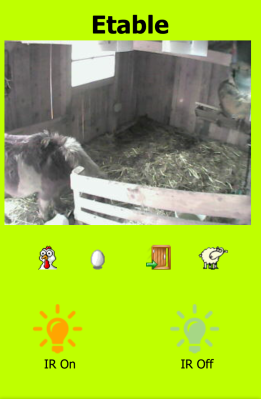

[Vince]’s livestock appears to consist of chickens and sheep at this point, and the fact that they share housing helped him to deploy some tech for both species. The chickens got an automated door that lets them out in the morning and shuts them in safely once they’ve returned to roost for the night – important protection against predators. The door is hoisted by a

[Vince]’s livestock appears to consist of chickens and sheep at this point, and the fact that they share housing helped him to deploy some tech for both species. The chickens got an automated door that lets them out in the morning and shuts them in safely once they’ve returned to roost for the night – important protection against predators. The door is hoisted by a