Commercially available motorized window blinds are a nice high-end touch for today’s automated home, but they tend to command a premium price. Seems silly to charge so much for what amounts to a gear motor and controller, which is why [James Wilcox] took matters into his own hands and came up with this simple and cheap wireless blind control.

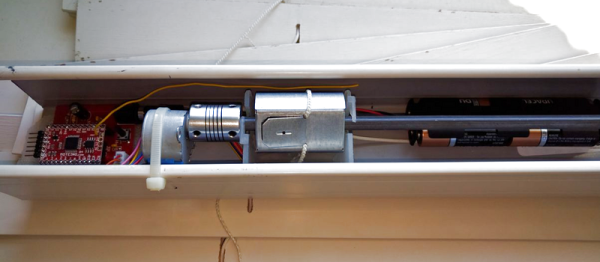

[James] started his project the sensible way, with a thorough analysis of the problem. Once COTS alternatives were eliminated – six windows would have been $1200 – he came up with a list of deliverables, including tilting to pre-determined positions, tilt-syncing across multiple windows, and long battery life. The hardware in the head rail of each blind ended up being a Moteino on a custom PCB for the drivers, a $2 stepper motor, and a four-AA battery pack. The Moteino in one blind talks to a BeagleBone Black over USB and wirelessly to the other windows for coordinated control. As for battery life, [James] capitalized on the Moteino’s low-power Listen Mode to reduce the current draw by about three orders of magnitude, which should equate to a few years between battery changes. And he did it all for only about $40 a window.

Window blinds seem to be a tempting target for hacking, whether it’s motorizing regular blinds or interfacing commercial motorized units into a home automation system. We like how compact this build is, and wonder if it could be offered as an aftermarket add-on for manual blinds.

Continue reading “Compact Controllers Automate Window Blinds”