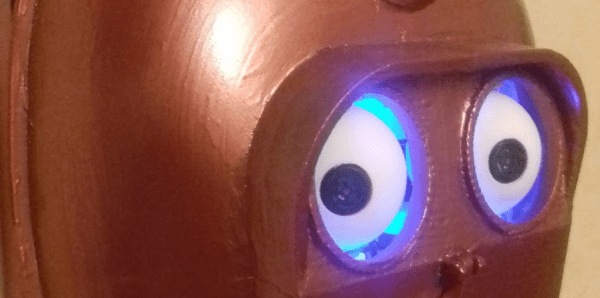

While sick with the flu a few months ago, [CroMagnon] had a vision. A face with eyes that would follow you – no matter where you walked in the room. He brought this vision to life in the form of Gawkerbot. This is no static piece of art. Gawkerbot’s eyes slowly follow you as you walk through its field of vision. Once the robot has fixed its gaze upon you, the eyes glow blue. It makes one wonder if this is an art piece, or if the rest of the robot is about to pop through the wall and attack.

Gawkerbot’s sensing system is rather simple. A PIR sensor detects motion in the room. If any motion is detected, two ultrasonic sensors which make up the robot’s pupils start taking data. Code running on an ATmega328 determines if a person is detected on the left or right, and moves the eyes appropriately.

[CroMagnon] used an old CD-ROM drive optics sled to move Gawkerbot’s eyes. While the motor is small, the worm drive has plenty of power to move the 3D-printed eyes and linkages. Gawkerbot’s main face is a 3D-printed version of a firefighter’s smoke helmet.

The ultrasonic sensors work, but it took quite a bit of software to tame the jitters noisy data stream. [CroMagnon] is thinking of using PIR sensors on Gawkerbot 2.0. Ultrasonic transducers aren’t just for sensing. Given enough power, you can solder with them. Ultrasonics even work for wireless communications.

Check out the video after the break to see Gawkerbot in action.