You’d think pool should be an easy game for a robot to play, right? It’s all math — geometry to figure out the angles and basic physics to deal with how much force is needed to move the balls. On top of that, it’s constrained to just two dimensions, so it should be a breeze.

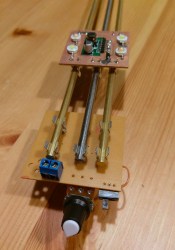

Any pool player will tell you there’s much, much more to the game in real life, but still, a robot to play pool against would be a neat trick. As a move toward that goal, [BVarv] wisely decided on a miniature mockup of a pool-playing robot, and in the process reinvented the pool table itself. Realizing that a tracked or wheeled robot would have a tough time maneuvering around the base of a traditional pool table, his model pool table is a legless design that looks like something from IKEA. But the pedestal support allows the robot to be attached to the table and swing around in a full circle, and this allowed him to work through the kinematics as shown in the charming stop-action video below.

[BVarv] has gotten as far as motion control on the swing axis, as well as on the arms that will eventually hold the cue. He plans overhead image analysis for identifying shots, and of course there’s the whole making it full-size thing to do. We’d love to play a game or two against a bot, so we hope he gets there. In the meantime, how about a little robo-air hockey?

Continue reading “Pool Playing Robot Destined For Trouble In River City”