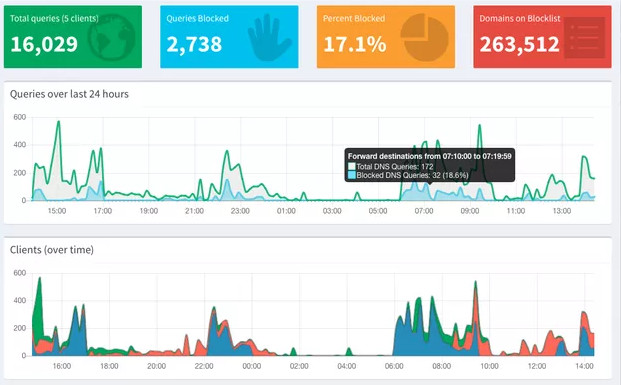

Pi-hole is an open source project to turn that Raspberry Pi collecting dust in your drawer into a whole-network ad blocking appliance. Not only does it stop ads from showing up on all your computers and mobile devices, it also keeps track of how many ads have been blocked and where they came from. Just in case you wanted to know how many thousands of ads you missed out on for a given time period.

While the graphs generated in the web interface of Pi-hole are slick and all, what if you just wanted a quick way of visualizing how effective your ad blocking system is? You’re not so much worried about the exact figures, you just want something to blink away on your desk and let you know all those ads are going to

While the graphs generated in the web interface of Pi-hole are slick and all, what if you just wanted a quick way of visualizing how effective your ad blocking system is? You’re not so much worried about the exact figures, you just want something to blink away on your desk and let you know all those ads are going to /dev/null. Enter the aptly named pi-hole-visualizer by [simianAstronaut].

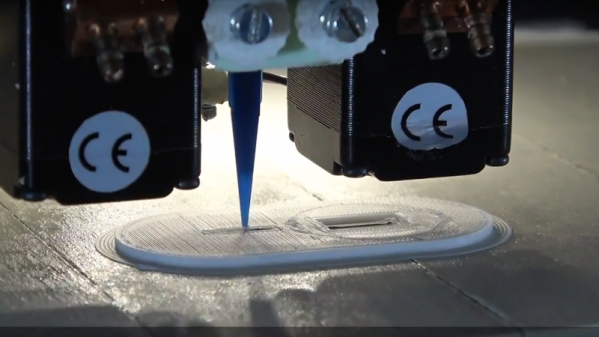

With the addition of a Sense HAT to the Pi running the ad blocking, this Python script will generate an animated visualization that can be easily interpreted even from a distance. The primary display is a bar graph of DNS traffic, where the height and color of each column indicate relative activity within a specific time interval. A second screen shows a spiral graph which gives you an idea of what percentage of ads were blocked before they hit your devices.

An array of options can be given to the script from the command line; controlling both physical aspects of the display like orientation and LED brightness, as well the configurable parameters for the different available visualizations. As an added bonus, there’s also support for using the Sense HAT joystick to switch between modes interactively.

Turning the Raspberry Pi into an ad blocking appliance goes back to the olden days of the original Raspberry Pi, but it’s interesting to see how advanced the concept has become. Just remember, not all ads are bad.