For most of the history of industrial electronics, solder has been pretty boring. Mix some lead with a little tin, figure out how to wrap it around a thread of rosin, and that’s pretty much it. Sure, flux formulations changed a bit, the ratio of lead to tin was tweaked for certain applications, and sometimes manufacturers would add something exotic like a little silver. But solder was pretty mundane stuff.

Then in 2003, the dull gray world of solder got turned on its head when the European Union adopted a directive called Restriction of Hazardous Substances, or RoHS. We’ve all seen the little RoHS logos on electronics gear, and while the directive covers ten substances including mercury, cadmium, and hexavalent chromium, it has been most commonly associated with lead solder. RoHS, intended in part to reduce the toxicity of an electronic waste stream that amounts to something like 50 million tons a year worldwide, marked the end of the 60:40 alloy’s reign as the king of electrical connections, at least for any products intended for the European market, when it went into effect in 2006.

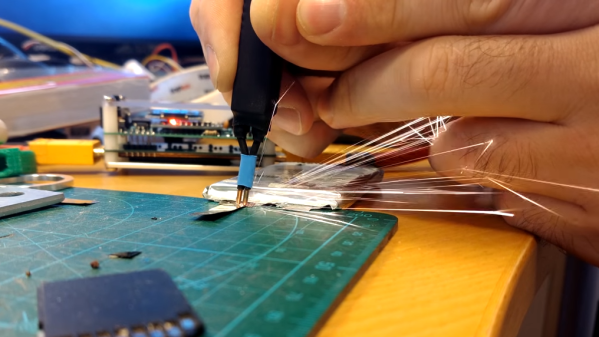

Did you ever see a thin metal tab bonded to a battery terminal with little pock marks? That’s the work of a spot welder. Spot welding is one of those processes that doesn’t offer much in the way of alternatives; either one uses a spot welder to do the job right, or one simply does without. That need is what led [Erwin Ried] to purchase a small, battery-powered spot welder from a maker in Korea and

Did you ever see a thin metal tab bonded to a battery terminal with little pock marks? That’s the work of a spot welder. Spot welding is one of those processes that doesn’t offer much in the way of alternatives; either one uses a spot welder to do the job right, or one simply does without. That need is what led [Erwin Ried] to purchase a small, battery-powered spot welder from a maker in Korea and