Hooking up a laser to a CNC gantry isn’t exactly an Earth-shattering innovation, but it does make for a useful tool. Even a cheap diode laser mounted to an old 3D printer can do engraving, marking, or even light-duty cutting. But what about a laser engraver without the laser? Can that be of any use?

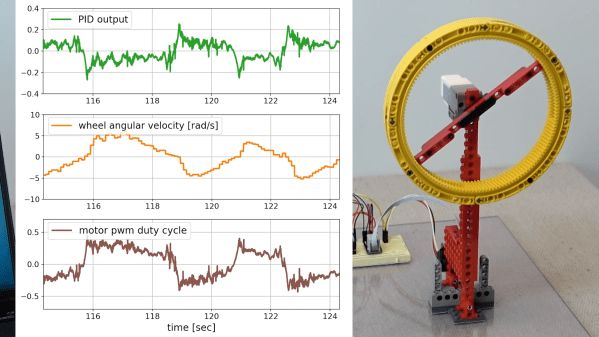

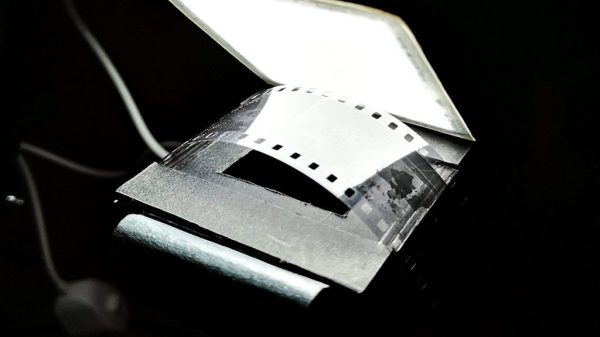

Apparently, the answer is yes, if you can harness the power of the sun. That’s what [Lucas] did with his solar-tracking CNC engraver, the build of which is shown in the video below. The idea is pretty simple — mount a decent-sized magnifying lens where the laser optics would normally go on a laser engraver, and point the thing at the sun. But as usual, the devil is in the details. The sun has a nasty habit of moving across the sky during the day, or at least appearing to, so [Lucas] has to add a couple of extra degrees of freedom to a regular X-Y CNC rig to track the sun. His tracking sensor is simplicity itself — four CdS photocells arranged with a pair of perpendicular shades, and an Arduino to drive the gimbals in the correct direction to keep all four sensors equally illuminated. He had some initial problems getting the jerkiness out of the control loop, but the tracker eventually kept the whole thing pointing right at the Sun.

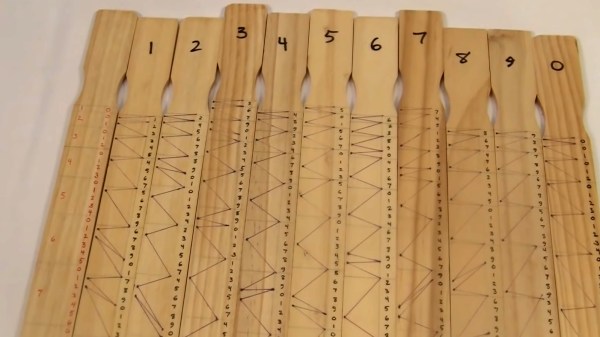

So how does it work? Not bad, actually — [Lucas] managed to burn some pretty detailed designs into a piece of wood using just the sun. He mentions adding a shutter to douse the cutting beam to allow raster patterns, but even better might be a servo-controlled iris diaphragm to modulate beam intensity and control for varying sun conditions. He might also check out this solar engraver we covered previously for some more ideas, too.

Continue reading “No-Laser CNC Engraver Is Something New Under The Sun”