When Hackaday announced winners of the 2014 Hackaday Prize, a bunch of hackers from Greece picked up the grand prize of $196,418 for their SatNOGS project – a global network of satellite ground stations for amateur Cubesats.

The design demonstrated an affordable ground station which can be built at low-cost and linked into a public network to leverage the benefits of satellites, even amateur ones. The social implications of this project were far-reaching. Beyond the SatNOGS network itself, this initiative was a template for building other connected device networks that make shared (and open) data a benefit for all. To further the cause, the SatNOGS team set up the Libre Space Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation with a mission to promote, advance and develop Libre (free and open source) technologies and knowledge for space.

The design demonstrated an affordable ground station which can be built at low-cost and linked into a public network to leverage the benefits of satellites, even amateur ones. The social implications of this project were far-reaching. Beyond the SatNOGS network itself, this initiative was a template for building other connected device networks that make shared (and open) data a benefit for all. To further the cause, the SatNOGS team set up the Libre Space Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation with a mission to promote, advance and develop Libre (free and open source) technologies and knowledge for space.

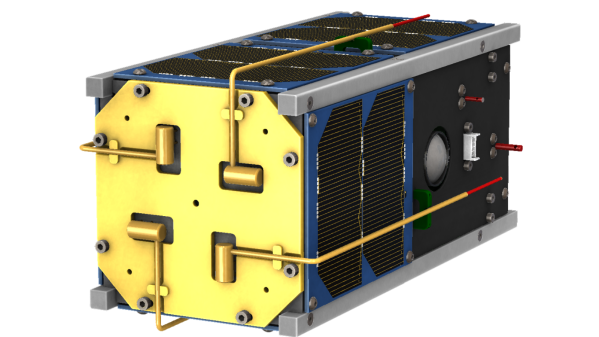

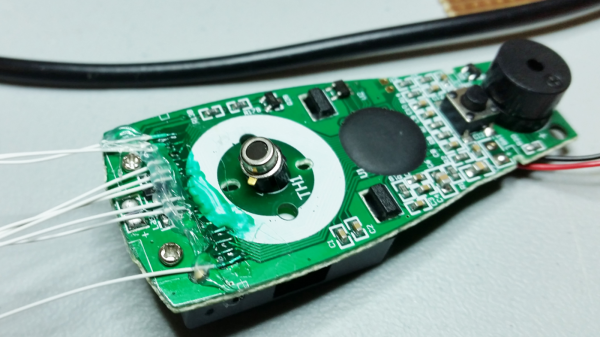

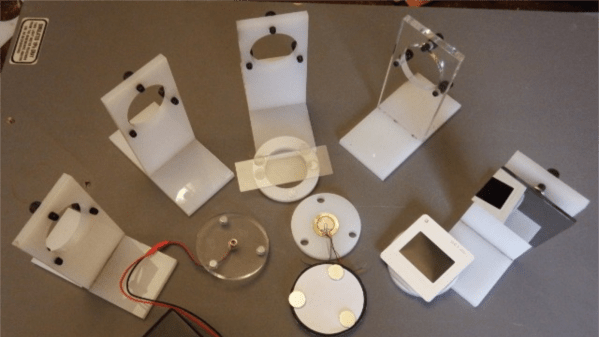

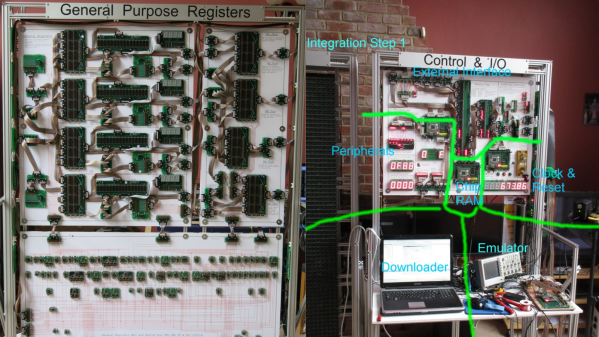

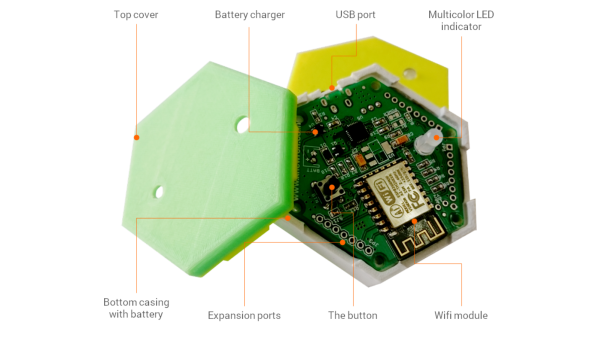

Now, the foundation, in collaboration with the University of Patras, is ready to launch UPSat – a 2U, Open Source Greek Cubesat format satellite as part of the QB50 international thermosphere research mission. The design aims to be maximally DIY, designing most subsystems from scratch. While expensive for the first prototype, they hope that documenting the open source hardware and software will help kickstart an ecosystem for space engineering and technologies. As of now, the satellite is fully built and undergoing testing and integration. In the middle of July, it will be delivered to Nanoracks to be carried on a SpaceX Dragon capsule and then launched from the International Space Station.

Continue reading “After The Prize: SatNOGS Builds Satellites”