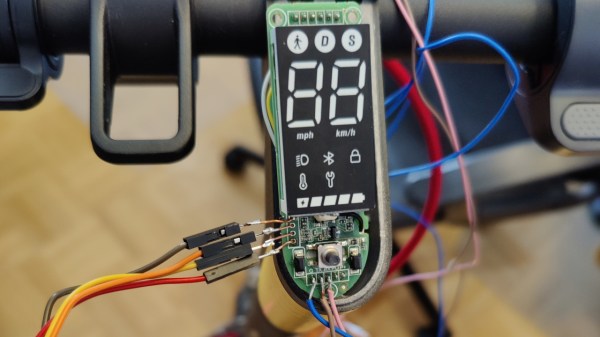

Scooter hacking is wonderful – you get to create a better scooter from a pre-made scooter platform, and sometimes you can do that purely through firmware modifications. Typically, hackers have been uploading firmware using Bluetooth OTA methods, and at some point, we’ve seen the always-popular Xiaomi scooters starting to get locked down. Today, we see [Daljeet Nandha] from [RoboCoffee] continue the research of the new Xiaomi scooter realities, where he finds that SWD flashing is way more of a viable avenue that we might’ve expected. Continue reading “Xiaomi Scooter Firmware Hacking Gets Hands-On”

Author: Arya Voronova514 Articles

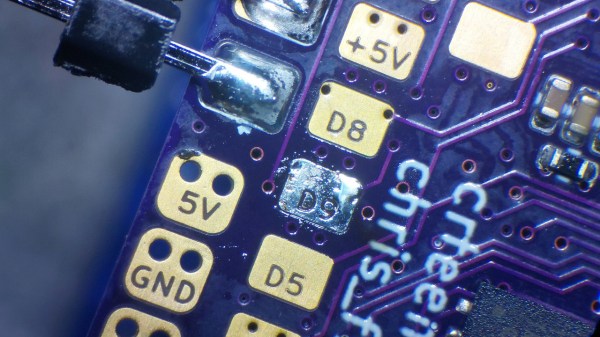

Silkscreen Busy? Put Labels Inside Pads

When making a PCB informative and self-documenting, there’s often just not enough space to silkscreen all the labels you want, and slowly but surely, you collect a set of tricks: using different through-hole pad shapes to denote ground or power pins, standardized pinouts for connectors, your own signal name shortening notations, and so on.

What if you have some large-ish signal pads on your board, and having the signal names on silkscreen just isn’t good enough? In this case, here’s a new trick for your toolkit: [Christoph] from [MakerProbe] shows us how he puts text directly inside the copper pads.

What you need is a set of Gerber files and a Python script. Technically, this ought to work with any PCB EDA, with [Christoph] using KiCad. You need to put the to-be-subtracted signal names on their very own layer, export Gerber files without features like aperture macros, then run the script. You’ll get a new copper layer as a result, it’s that simple. We also get a set of tips on what kinds of pads suit best and how to prepare them — and fancy-looking real-life examples. You get higher resolution than for on-silkscreen text, solderability isn’t impacted, and the labels are even visible after desoldering wires from the pads. What’s not to like?

Over on Twitter, [Makerprobe] have been doing things like 0201 tombstoning and BGA yield research – we say they’re worth a follow if you’d like to see someone pushing PCB boundaries! Innovative PCB design methods and tricks have a special spot in our hearts, what’s with things like this Tux-emblazoned desktop motherboard that’s also a guide on PCB aesthetics, and there’s a whole lot more you can do to make your PCBs pretty while preserving and even improving functionality. From turning rigid PCBs flexible to hiding components inside a PCB stack, there’s plenty of opportunities that we are yet to extract out of PCB world, and it’s lovely to see one more technique we can make use of.

Open-Source FaceID With RealSense

RealSense cameras have been a fascinating piece of tech from Intel — we’ve seen a number of cool applications in the hacker world, from robots to smart appliances. Unfortunately Intel did discontinue parts of the RealSense lineup at one point, specifically the LiDAR and face tracking-tailored models. Apparently, these haven’t been popular, and we haven’t seen these in hacks either. Until now, that is. [Lina] brings us a real-world application for the RealSense face tracking cameras, a FaceID application for Linux.

The project is as simple as it sounds: if the camera’s built-in face recognition module recognizes you, your lockscreen is unlocked. With the target being Linux, it has to tie into the Pluggable Authentication Modules (PAM) subsystem for authentication, and of course, there’s a PAM module for RealSense to go with it, aptly named pam_sauron. This module is written in Zig, a modern C-like language, so it’s both a good example of how to create your own PAM integrations, and a path towards doing that in a different language for once. As usual, there’s TODOs, like improving the UX and taking advantage of some security features RealSense cameras have, but it’s nevertheless a fun and self-sufficient application for one of the F4XX-series RealSense cameras in case you happen to own one.

Ever since the introduction of RealSense we’ve seen these cameras used in robotics and 3D scanning, thanks at least in part due to their ability to be used in Linux. Thankfully, Intel only discontinued the less popular RealSense cameras, which didn’t affect the main RealSense lineup, and the hacker-beloved depth cameras are still available for all of our projects. Wondering about the tech behind it? Here’s a teardown of a RealSense camera module intended for laptop use.

Server Network Cards Made Extra Cool

Using cheap and powerful server expansion cards in your desktop builds is a tempting option for many hackers. Of course, they don’t always fit mechanically or work perfectly; for instance, some server-purpose cards are designed for intense amounts of cooling that servers come with, and will overheat inside a relatively calm desktop case. Having encountered such a network card, [Chris] has developed and brought us the PCIce – a PCIe card that’s a holder and a controller for a 80mm fan.

The card gets fan 12V from the PCIe slot, and there’s an ATTiny to control the fan’s speed, letting you cycle through speeds with a single button press and displaying the current speed through LEDs. There’s a great amount of polish put into this card – from making it mechanically feature-complete with all the fancy fasteners, to longevity-oriented firmware that even makes sure to notice if the EEPROM-stored settings ever get corrupted. At the moment, the schematics and the ATTiny firmware are open-source, [Chris] has promised to publish hardware files after polishing them, and has also manufactured a batch of PCIce cards for sale.

When it comes to making use of cheap server-purpose cards, a cooling solution is good to see – we’ve generally seen adapters from proprietary form-factors, like this FlexLOM adapter from [TobleMiner] to make use of cheap high-throughput network cards with slightly differing mechanical dimensions and pinouts. Every batch of decommissioned server cards has some potential with only a slight hitch or two, and it’s reassuring to see hackers make their eBay finds really work for them.

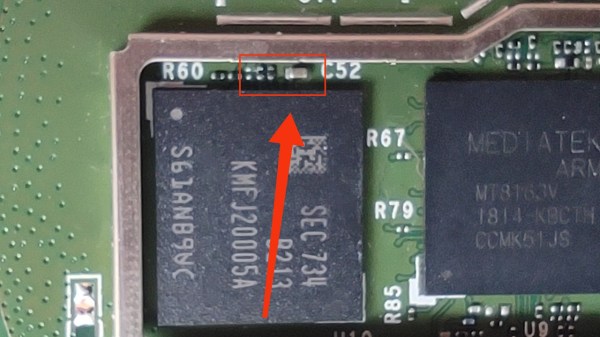

Squeezing Secrets Out Of An Amazon Echo Dot

As we have seen time and time again, not every device stores our sensitive data in a respectful manner. Some of them send our personal data out to third parties, even! Today’s case is not a mythical one, however — it’s a jellybean Amazon Echo Dot, and [Daniel B] shows how to make it spill your WiFi secrets with a bit of a hardware nudge.

There’s been exploits for Amazon devices with the same CPU, so to save time, [Daniel] started by porting an old Amazon Fire exploit to the Echo Dot. This exploit requires tactically applying a piece of tin foil to a capacitor on the flash chip power rail, and it forces the Echo to surrender the contents of its entire filesystem, ripe for analysis. Immediately, [Daniel] found out that the Echo keeps your WiFi passwords in plain text, as well as API keys to some of the Amazon-tied services.

Found an old Echo Dot at a garage sale or on eBay? There might just be a WiFi password and a few API keys ripe for the taking, and who knows what other kinds of data it might hold. From Amazon service authentication keys to voice recognition models and maybe even voice recordings, it sounds like getting an Echo to spill your secrets isn’t all that hard.

We’ve seen an Echo hijacked into an always-on microphone before, also through physical access in the same vein, so perhaps we all should take care to keep our Echoes in a secure spot. Luckily, adding a hardware mute switch to Amazon’s popular surveillance device isn’t all that hard. Though that won’t keep your burned out smart bulbs from leaking your WiFi credentials.

PCIe For Hackers: Extracting The Most

So, you now know the basics of approaching PCIe, and perhaps you have a PCIe-related goal in mind. Maybe you want to equip a single-board computer of yours with a bunch of cheap yet powerful PCIe WiFi cards for wardriving, perhaps add a second NVMe SSD to your laptop instead of that Ethernet controller you never use, or maybe, add a full-size GPU to your Raspberry Pi 4 through a nifty adapter. Whatever you want to do – let’s make sure there isn’t an area of PCIe that you aren’t familiar of.

Splitting A PCIe Port

You might have heard the term “bifurcation” if you’ve been around PCIe, especially in mining or PC tinkering communities. This is splitting a PCIe slot into multiple PCIe links, and as you can imagine, it’s quite tasty of a feature for hackers; you don’t need any extra hardware, really, all you need is to add a buffer for REFCLK. See, it’s still needed by every single extra port you get – but you can’t physically just pull the same clock diffpair to all the slots at once, since that will result in stubs and, consequently, signal reflections; a REFCLK buffer chip takes the clock from the host and produces a number of identical copies of the REFCLK signal that you then pull standalone. You might have seen x16 to four NVMe slot cards online – invariably, somewhere in the corner of the card, you can spot the REFCLK buffer chip. In a perfect scenario, this is all you need to get more PCIe out of your PCIe.

You might have heard the term “bifurcation” if you’ve been around PCIe, especially in mining or PC tinkering communities. This is splitting a PCIe slot into multiple PCIe links, and as you can imagine, it’s quite tasty of a feature for hackers; you don’t need any extra hardware, really, all you need is to add a buffer for REFCLK. See, it’s still needed by every single extra port you get – but you can’t physically just pull the same clock diffpair to all the slots at once, since that will result in stubs and, consequently, signal reflections; a REFCLK buffer chip takes the clock from the host and produces a number of identical copies of the REFCLK signal that you then pull standalone. You might have seen x16 to four NVMe slot cards online – invariably, somewhere in the corner of the card, you can spot the REFCLK buffer chip. In a perfect scenario, this is all you need to get more PCIe out of your PCIe.

Loudmouth DJI Drones Tell Everyone Where You Are

Back when commercial quadcopters started appearing in the news on the regular, public safety was a talking point. How, for example, do we keep them away from airports? Well, large drone companies didn’t want the negative PR, so some voluntarily added geofencing and tracking mechanisms to their own drones.

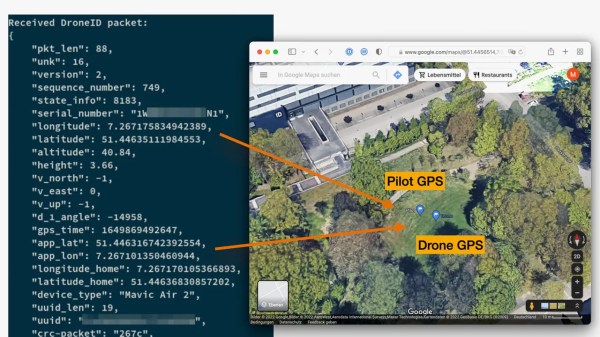

When it comes to DJI, one such mechanism is DroneID: a beacon on the drone itself, sending out a trove of data, including its operator’s GPS location. DJI also, of course, sells the Aeroscope device that receives and decodes DroneID data, declared to be for government use. As it often is with privacy-compromising technology, turns out it’s been a bigger compromise than we expected.

Questions started popping up last year, as off-the-shelf quadcopters (including those made by DJI) started to play a part in the Russo-Ukrainian War. It didn’t take long for Ukrainian forces to notice that launching a DJI drone led to its operators being swiftly attacked, and intel was that Russia got some Aeroscopes from Syria. DJI’s response was that their products were not meant to be used this way, and shortly thereafter cut sales to both Russia and Ukraine.

But security researchers have recently discovered the situation was actually worse than we expected. Back in 2022, DJI claimed that the DroneID data was encrypted, but [Kevin Finisterre]’s research proved that to be a lie — with the company finally admitting to it after Verge pushed them on the question. It wouldn’t even be hard to implement a worse-than-nothing encryption that holds up mathematically. However, it seems, DroneID doesn’t even try: here’s a GitHub repository with a DroneID decoder you can use if you have an SDR dongle.

Sadly, the days of companies like DJI standing up against the anti-copter talking points seem to be over, Now they’re setting an example on how devices can subvert their owners’ privacy without reservation. Looks like it’s up to hackers on the frontlines to learn how to excise DroneID, just like we’ve done with the un-nuanced RF power limitations, or the DJI battery DRM, or transplanting firmware between hardware-identical DJI flight controller models.

Continue reading “Loudmouth DJI Drones Tell Everyone Where You Are”