The Elegoo Mars is an affordable SLA (resin-based) 3D printer, and there are probably few that have seen more mods and experimentation than [Jan Mrázek]’s machine. The final design of his DIY flexible build plate is a refinement of his original proof of concept, which proved a flexible build platform can be every bit as useful on an SLA printer as it is for FDM; instead of chiseling parts off a rigid build platform, simply pop the flexible steel sheet off the magnetic base and flex it slightly for a much easier part removal process. His original design worked, but had a few rough edges that have since been ironed out.

Fortunately, it’s a simple job for any metal fabrication shop and [Jan] got a variety of thicknesses cut very cheaply. It turns out that the sweet spot is 0.3 mm (although 0.2 mm is a better choice for particularly fragile parts.) [Jan] also suggests cutting the sheet a few millimeters larger than the build platform; it’s much easier to peel the sheet off the magnetic base when one can get a fingertip under an edge, after all.

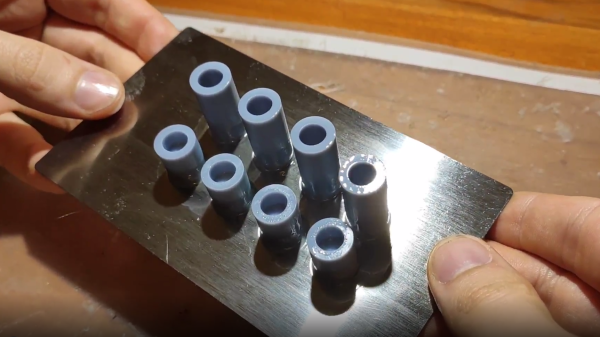

The magnetic base that the steel sheet sticks to is very simple: [Jan] converted a stock build platform by mounting an array of 20 x 20 x 1 mm magnets with 3M adhesive mounting tape. He was worried that resin might seep in between the magnets and cause a problem, perhaps even interfering with the adhesive; but so far it seems to be working very well. Resin is viscous enough that it never penetrates far into the gaps, and no effect on the adhesive has been observed so far.

Watch how easily parts are removed in the short video embedded below, in which [Jan] demonstrates his latest platform design.

Continue reading “Improved Flexible Build Plate For SLA Is Ready To Rock”