The James Webb Space Telescope’s array of eighteen hexagonal mirrors went through an intricate (and lengthy) alignment and calibration process before it could begin its mission — but the process is far from being a one-and-done. Keeping the telescope aligned and performing optimally requires constant work from its own team dedicated to the purpose.

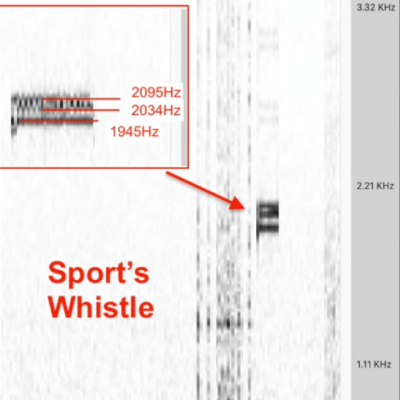

Alignment of the optical elements in JWST are so fine, and the tool is so sensitive, that even small temperature variations have an effect on results. For about twenty minutes every other day, the monitoring program uses a set of lenses that intentionally de-focus images of stars by a known amount. These distortions contain measurable features that the team uses to build a profile of changes over time. Each of the mirror segments is also checked by being imaged selfie-style every three months.

This work and maintenance plan pays off. The team has made over 25 corrections since its mission began, and JWST’s optics continue to exceed specifications. The increased performance has direct payoffs in that better data can be gathered from faint celestial objects.

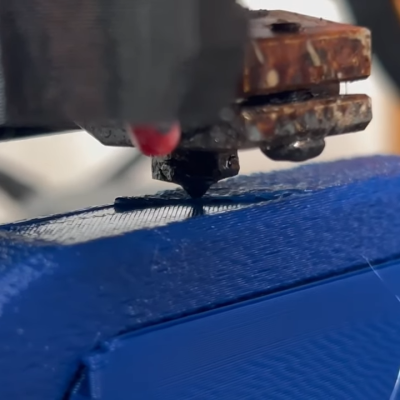

JWST was fantastically ambitious and is extremely successful, and as a science instrument it is jam-packed with amazing bits, not least of which are the actuators responsible for adjusting the mirrors.