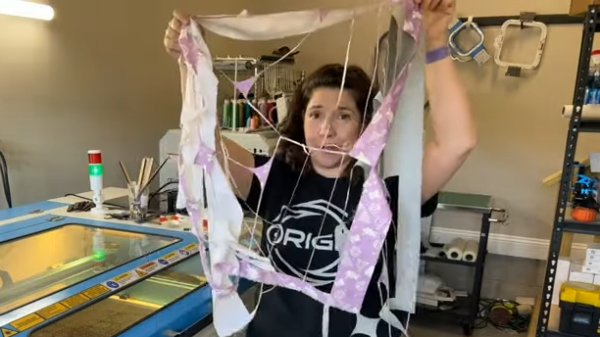

Fabric must be cut before it can be turned into something else, and [fiercekittenz] shows how a laser cutter can hit all the right bases to save a lot of time on the process. She demonstrates processing three layers of fabric at once on a CO2 laser cutter, cutting three bags’ worth of material in a scant 1 minute and 29 seconds.

The three layers are a PU (polyurethane) waterproof canvas, a woven liner, and a patterned cotton canvas. The laser does a fantastic job of slicing out perfectly formed pieces in no time, and its precision means minimal waste. The only gotcha is to ensure materials are safe to laser cut. For example, PU-based canvas is acceptable, but PVC-based materials are not. If you want to skip the materials discussion and watch the job, laying the fabric in the machine starts around [3:16] in the video.

[fiercekittenz] acknowledges that her large 100-watt CO2 laser cutter is great but points out that smaller or diode-based laser machines can perfectly cut fabric under the right circumstances. One may have to work in smaller batches, but it doesn’t take 100 watts to do the job. Her large machine, for example, is running at only a fraction of its full power to cut the three layers at once.

One interesting thing is that the heat of the laser somewhat seals the cut edge of the PU waterproof canvas. In the past, we’ve seen defocused lasers used to weld and seal non-woven plastics like those in face masks, a task usually performed by ultrasonic welding. The ability for a laser beam to act as both “scissors” and “glue” in these cases is pretty interesting. You can learn all about using a laser cutter instead of fabric scissors in the video embedded below.

Continue reading “Take The Tedium Out Of Fabric Cutting, Make The Laser Do It”