[Walker] has a very interesting new project: a completely different take on a self-destructing USB drive. Instead of relying on encryption or other “visible” security features, this device looks and works like an utterly normal USB drive. The only difference is this: if an unauthorized person plugs it in, there’s no data. What separates authorized access from unauthorized? Wet fingers.

It sounds weird, but let’s walk through the thinking behind the concept. First, encryption is of course the technologically sound and correct solution to data security. But in some environments, the mere presence of encryption technology can be considered incriminating. In such environments, it is better for the drive to appear completely normal.

The second part is the access control; the “wet fingers” part. [Walker] plans to have hidden electrodes surreptitiously measure the resistance of a user’s finger when it’s being plugged in. He says a dry finger should be around 1.5 MΩ, but wet fingers are more like 500 kΩ.

But why detect a wet finger as part of access control? Well, what’s something no normal person would do right before plugging in a USB drive? Lick their finger. And what’s something a microcontroller should be able to detect easily without a lot of extra parts? A freshly-licked finger.

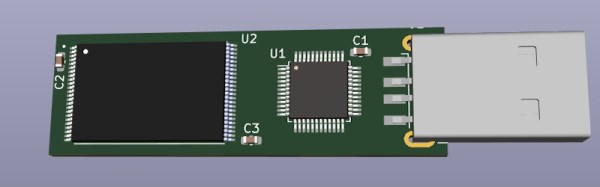

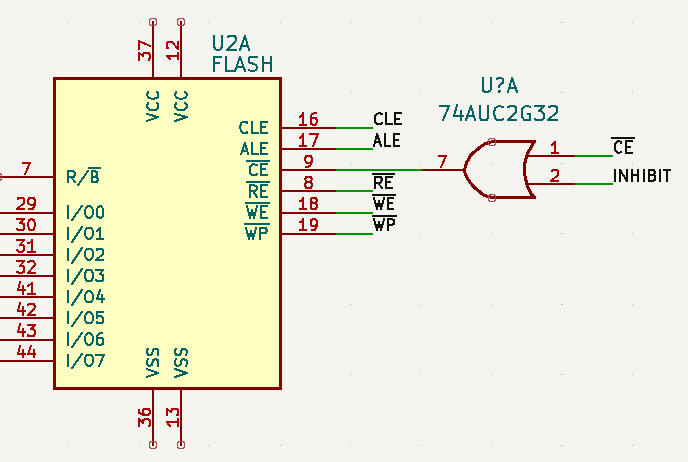

Of course, detecting wet skin is only half the equation. You still need to implement a USB Mass Storage device, and that’s where things get particularly interesting. Even if you aren’t into the covert aspect of this device, the research [Walker] has done into USB storage controllers and flash chips, combined with the KiCad footprints he’s already put together means this open source project will be a great example for anyone looking to roll their own USB flash drives.

Regular readers may recall that [Walker] was previously working on a very impressive Linux “wall wart” intended for penetration testers, but the chip shortage has put that ambitious project on hold for the time being. As this build looks to utilize less exotic components, hopefully it can avoid a similar fate.