On August 21, 2017, the moon will cast its shadow across most of North America, with a narrow path of totality tracing from Oregon to South Carolina. Tens of millions of people will have a chance to see something that the continental US hasn’t seen in ages — a total eclipse of the sun. Will you be ready?

The last time a total solar eclipse visited a significantly populated section of the US was in March of 1970. I remember it well as a four-year-old standing on the sidewalk in front of my house, all worked up about space already in those heady days of the Apollo program, gazing through smoked glass as the moon blotted out the sun for a few minutes. Just watching it was exhilarating, and being able to see it again and capitalize on a lifetime of geekiness to heighten the experience, and to be able to share it with my wife and kids, is exciting beyond words. But I’ve only got eight months to lay my plans! Continue reading “Get Ready For The Great Eclipse Of 2017”

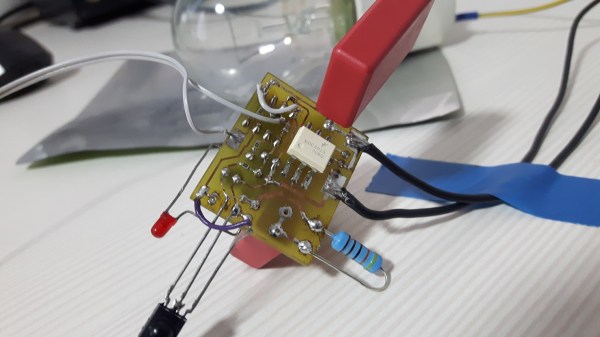

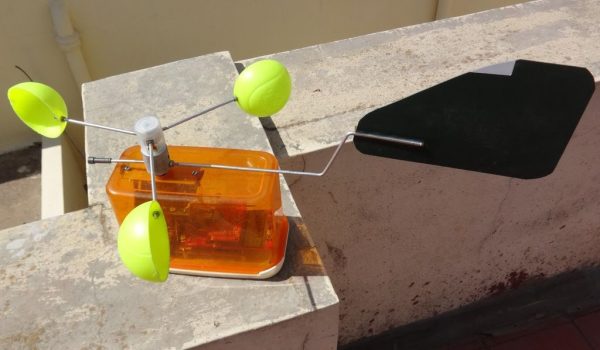

We have to admit that when we first saw [Ajoy Raman]’s Instructables post, we figured that he used a universal motor to generate a voltage from the anemometer. But [Ajoy]’s solution to the coaxial shafts problem is far more interesting than that. A discarded universal motor donated its rotor and bearings. The windings were stripped off the assembly leaving nothing but the commutator. 1kΩ SMD resistors were soldered across adjacent commutator sections to form a series resistance of 22kΩ with taps every 1k, allowing 0 to 2.2V to be read to the ADC of a microcontroller depending on the angle of the vane.

We have to admit that when we first saw [Ajoy Raman]’s Instructables post, we figured that he used a universal motor to generate a voltage from the anemometer. But [Ajoy]’s solution to the coaxial shafts problem is far more interesting than that. A discarded universal motor donated its rotor and bearings. The windings were stripped off the assembly leaving nothing but the commutator. 1kΩ SMD resistors were soldered across adjacent commutator sections to form a series resistance of 22kΩ with taps every 1k, allowing 0 to 2.2V to be read to the ADC of a microcontroller depending on the angle of the vane.