As if the prospect of having everyone’s favorite scripting language ported over weren’t enough to get you to install MicroPython on a spare ESP8266, there is now a contest for that. Over on Hackaday.io the MicroPython on ESP8266 contest is under way and you’ve only got until the end of August to submit your creation.

The prizes? First place gets an OpenMV camera board because [Radomir], who’s running the contest, has an extra one. OK, it’s not as lush as the corporate-sponsored goody-bag that we’ve got running in the Hackaday Prize, but there’s no reason that you can’t enter both. And if anyone wants to throw some more goodies into the pot, I’m sure they’d be welcome.

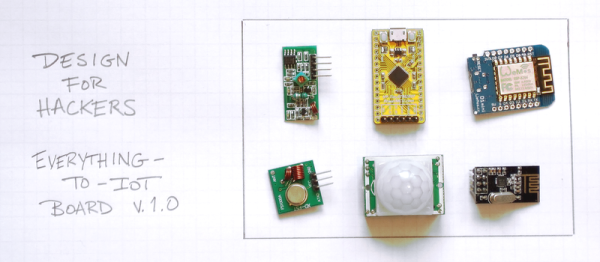

The rules are simple: use an ESP8266 or ESP8285 with MicroPython and post the project up on Hackaday.io. Bonus points are given for creating new libraries or hardware drivers. Basically, this just gives you an extra reason to get in there and play around. How cool is that?

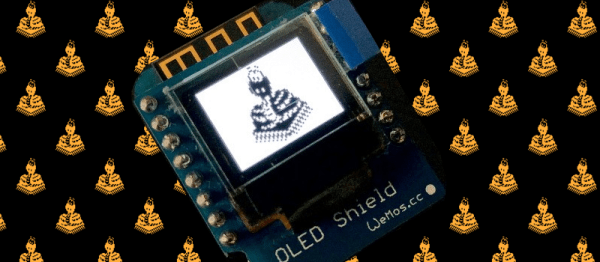

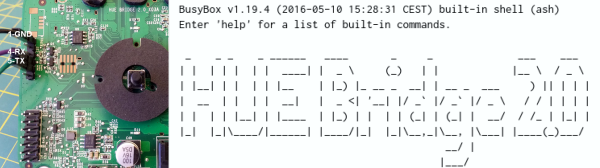

If you need a start-up on MicroPython on the ESP8266, the official tutorial is great. We wrote up a first-look review of running MicroPython on the WeMos D1 hardware, but were plagued with (re-)flashing difficulties, so we’re going to have to give it another go.