We are fortunate enough to have a huge choice of single-board computers before us, not just those with a bare-metal microcontroller, but also those capable of running fully-fledged general purpose operating systems such as GNU/Linux. The Raspberry Pi is probably the best known of this latter crop of boards, and it has spawned a host of competitors with similarly fruity names. With an entire cornucopia to choose from, it takes a bit more than evoking a berry to catch our attention. The form factors are becoming established and the usual SoCs are pretty well covered already, show us something we haven’t seen before!

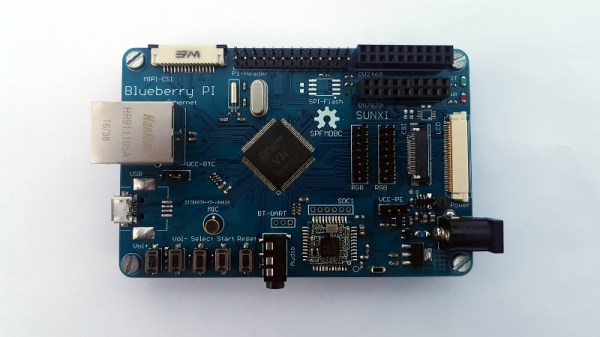

[Marcel Thürmer] may have managed that feat, with his Blueberry Pi. On the face of it this is just Yet Another SBC With A Fruity Pi Name, but what caught our attention is that unlike all the others, this is one you can build yourself if you want. It’s entirely open-source, but it differs from other boards that release their files to the world in that it manages to keep construction within the realm of what is possible on the bench rather than the pick-and-place. He’s done this by choosing an Alwinner V3, an SoC originally produced for the action camera market that is available in a readily-solderable TQFP package. It’s a choice that has allowed him to pull off another constructor-friendly feat: the board is only two layers, so it won’t break the bank to have it made.

It’s fair to say that the Allwinner V3 (PDF) isn’t the most powerful of Linux-capable SoCs, but it has the advantage of built-in RAM to avoid more tricky soldering. With only 64Mb of memory, it’s never going to be a powerhouse, but it does pack onboard Ethernet, serial and parallel camera interfaces, and audio as well as the usual interfaces you’d expect. There is no video support on the Blueberry Pi, but the chip has LVDS for an LCD panel, so it’s not impossible to imagine something could be put together. Meanwhile, all you need to know about the board can be found on its GitHub repository. There is no handy OS image to download, u-boot instructions are provided to build your own. We suspect if you’re the kind of person who is building a Blueberry Pi though this may not present a problem to you.

We hope the Blueberry Pi receives more interest, develops a wider community, and becomes a board with a solid footing. We like its achievement of being both a powerful platform and one that is within reach of the home constructor, and we look forward to it being the subject of more attention.

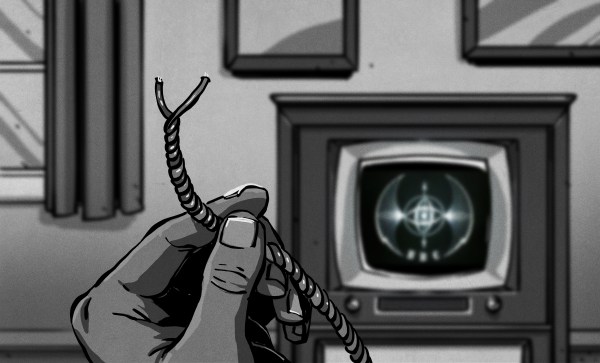

Housed on a standard-sized British electrical fascia was a 12-position rotary switch, marked with letters A through L. An unexpected thing to see in the 21st century and one probably unfamiliar to most people under about 40, I’d found something I’d not seen since my university days in the early 1990s: a Rediffusion selector switch.

Housed on a standard-sized British electrical fascia was a 12-position rotary switch, marked with letters A through L. An unexpected thing to see in the 21st century and one probably unfamiliar to most people under about 40, I’d found something I’d not seen since my university days in the early 1990s: a Rediffusion selector switch.