Give your grizzled and cramped hands a break from stuffing boards with surface mount components. This is the job of pick and place machine, and over the years these tools of the trade for Printed Circuit Board Assembly (PCBA) have gotten closer to reality for the home shop; with some models diving below the $10,000 mark. But if you’re not doing it professionally, those are still unobtanium.

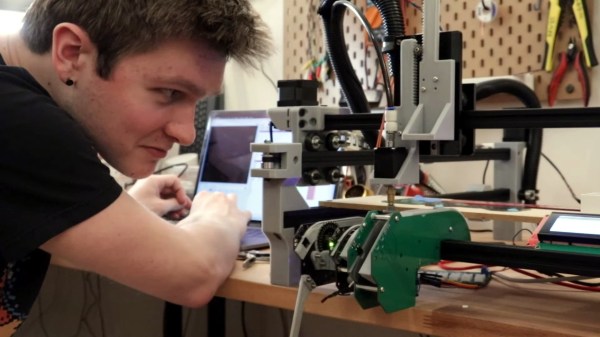

The cost of this one, on the other hand, could be explained away as a project in itself. You’re not buying a $450 shop tool, you’re purchasing materials to chase the fever dream of building an open source pick and place machine. There are two major parts here, an X/Y/Z machine tool that can also rotate the vacuum-based parts picker, and the feeders that reel out components to be placed. All of this is working, but there’s still a long road to travel before it becomes a set and forget machine.

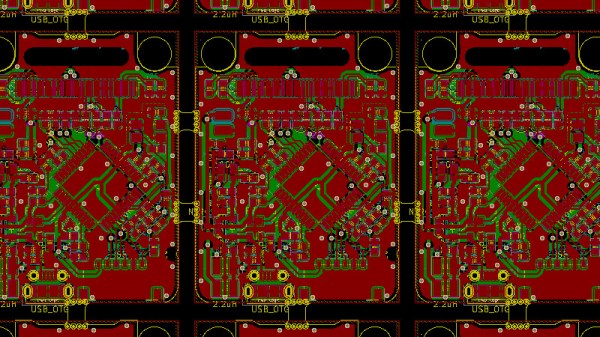

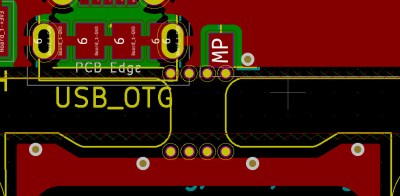

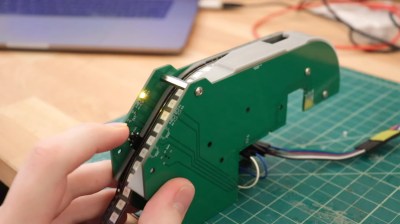

The rubber hits the road in two ways with pick and place machines: the feeders, and the optical placement. The feeders are where [Stephen Hawes] has done a ton of work, all shown in his video series that began back in January. The stackup of PCBs and 3D-prints hangs on the front rail of the gantry assembly, is adjustable for tape widths, and uses an interesting PCB encoder wheel and worm-gear for fine-tuning the feed. [Stephen’s] main controller board, a RAMPS shield for and Arduino Mega that runs a customized version of Marlin, can work with up to 32 of these feeders.

The rubber hits the road in two ways with pick and place machines: the feeders, and the optical placement. The feeders are where [Stephen Hawes] has done a ton of work, all shown in his video series that began back in January. The stackup of PCBs and 3D-prints hangs on the front rail of the gantry assembly, is adjustable for tape widths, and uses an interesting PCB encoder wheel and worm-gear for fine-tuning the feed. [Stephen’s] main controller board, a RAMPS shield for and Arduino Mega that runs a customized version of Marlin, can work with up to 32 of these feeders.

So far it doesn’t look like he’s tackled a vision system, although the Bill of Materials does include “Downwards Camera”, confirming this is a planned feature. Vision is crucial in commercial offerings, with at least one downward camera for precise board positioning, and often an up-facing camera as well to ensure component position and orientation (if not multiple cameras for each purpose). Without these, the machine would be dead reckoning and that can lead to drift over the size of the board and the duration of the placement run as well as axial misalignment. Adding vision shouldn’t be a ground-up effort though, as [Stephen] chose to use OpenPnP to drive the machine and that project already has vision support. This will be much simpler to add when compared to the complexity of the feeders.

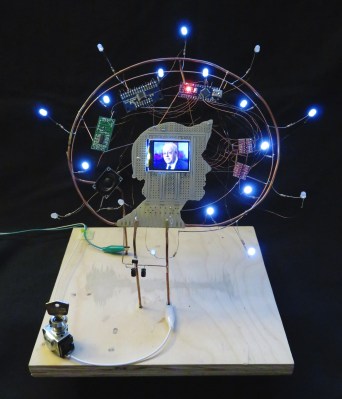

[Stephen] admits that much work still needs to be done and he would love to have help dialing in the performance of the feeder design, and fleshing out features on the road to perfection. Although we suspect that as in the early days of bootstrapping 3D printers, a project like this can never be truly finished. At least it’ll make his next run of LED glowties a lot easier to fabricate.

Continue reading “Open Source Pick And Place Has A $450 BOM Cost”