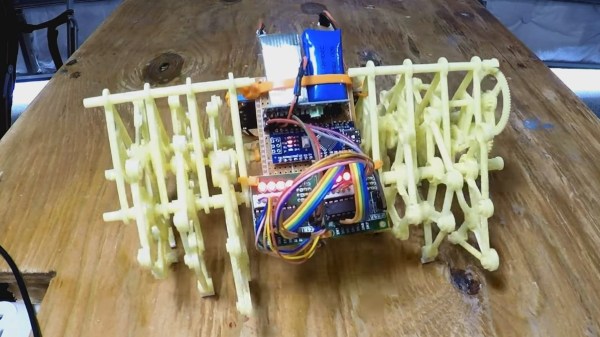

One way to design an underwater monitoring device is to take inspiration from nature and emulate an underwater creature. [Michael Barton-Sweeney] is making devices in the shape of, and functioning somewhat like, clams for his open source underwater distributed sensor network.

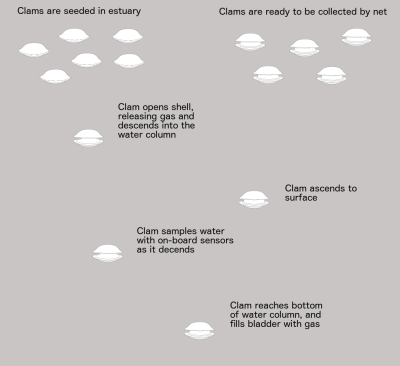

The clams contain the electronics, sensors, and means of descending and ascending within their shells. A bunch of them are dropped overboard on the surface. Their shells open, allowing the gas within to escape and they sink. As they descend they sample the water. When they reach the bottom, gas fills a bladder and they ascend back to the surface with their data where they’re collected in a net.

The clams contain the electronics, sensors, and means of descending and ascending within their shells. A bunch of them are dropped overboard on the surface. Their shells open, allowing the gas within to escape and they sink. As they descend they sample the water. When they reach the bottom, gas fills a bladder and they ascend back to the surface with their data where they’re collected in a net.

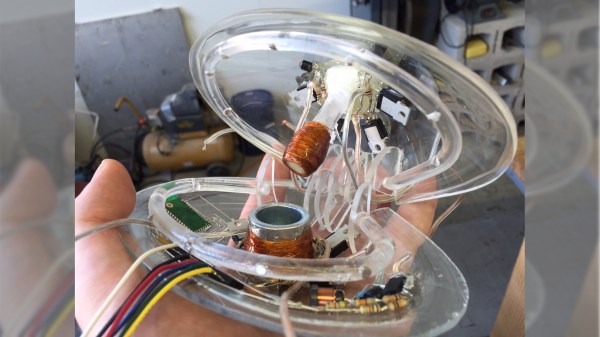

Thus far he’s made a few clams using acrylic for the shells which he’s blown himself. He soldered the electronics together free-form and gave them a conformal coating of epoxy. He’s also used a thermistor as a stand-in for other sensors and is already working on a saturometer, used for measuring the total dissolved gas (TDG) in the water. Knowing the TDG is useful for understanding and mitigating supersaturation of water which can lead to fish kills.

He’s also given a lot of thought into the materials used since some clams may not make it back up and would have to degrade or be benign where they rest. For example, he’s been using a lithium battery for now but would like to use copper on one shell and zinc on another to make a salt water battery, if he can make it produce enough power. He’s also considering using 3D printing since PLA is biodegradable. However, straight PLA could be subject to fouling by underwater organisms and would require cleaning, which would be time-consuming. PLA becomes soft when heated in a dishwasher and so he’s been looking into a PLA and calcium carbonate filament instead.

Check out his hackaday.io page where he talks about all these and more issues and feel free to make any suggestions.

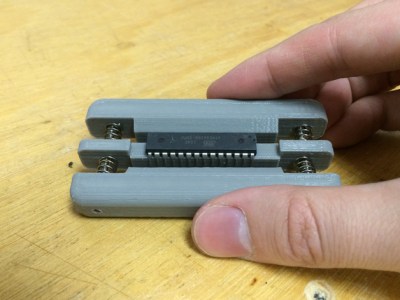

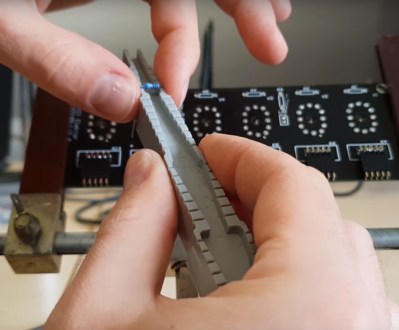

Fresh from the factory Dual Inline Package (DIP) chips come with their legs splayed every so slightly apart — enough to not fit into the carefully designed footprints on a circuit board. You may be used to imprecisely bending them by hand on the surface of the bench. [Marco] is more refined and shows off a neat little spring loaded tool that just takes a couple of squeezes to neatly bend both sides of the DIP, leaving every leg the perfect angle. Shown here is

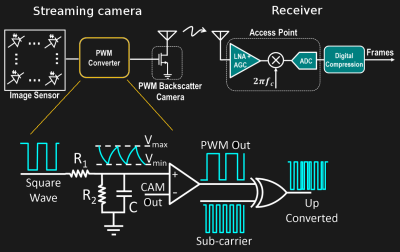

Fresh from the factory Dual Inline Package (DIP) chips come with their legs splayed every so slightly apart — enough to not fit into the carefully designed footprints on a circuit board. You may be used to imprecisely bending them by hand on the surface of the bench. [Marco] is more refined and shows off a neat little spring loaded tool that just takes a couple of squeezes to neatly bend both sides of the DIP, leaving every leg the perfect angle. Shown here is  Another tool which caught our eye is the one he uses for bending the metal film resistor leads: the “Biegelehre” or lead bending tool. You can see that [Marco’s] tool has an angled trench to account for different resistor body widths, with stepped edges for standard PCB footprint spacing. We bet you frequently use the same resistor bodies so 3D printing is made easier by

Another tool which caught our eye is the one he uses for bending the metal film resistor leads: the “Biegelehre” or lead bending tool. You can see that [Marco’s] tool has an angled trench to account for different resistor body widths, with stepped edges for standard PCB footprint spacing. We bet you frequently use the same resistor bodies so 3D printing is made easier by