When last we saw [xoreaxeax], he had built a lens-less optical microscope that deduced the structure of a sample by recording the diffraction patterns formed by shining a laser beam through it. At the time, he noted that the diffraction pattern was a frequency decomposition of the specimen’s features – in other terms, a Fourier transform. Now, he’s back with an explanation of why this is, deriving equations for the Fourier transform from the first principles of diffraction (German video, but with auto-translated English subtitles. Beware: what should be “Huygens principle” is variously translated as “squirrel principle,” “principle of hearing,” and “principle of the horn”).

The first assumption was that light is a wave that can be adequately represented by a sinusoidal function. For the sake of simplicity (you’ll have to take our word for this), the formula for a sine wave was converted to a complex number in exponential form. According to the Huygens principle, when light emerges from a point in the sample, it spreads out in spherical waves, and the wave at a given point can therefore be calculated simply as a function of distance. The principle of superposition means that whenever two waves pass through the same point, the amplitude at that point is the sum of the two. Extending this summation to all the various light sources emerging from the sample resulted in an infinite integral, which simplified to a particular form of the Fourier transform.

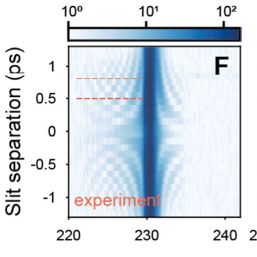

One surprising consequence of the relation is the JPEG representation of a micrograph of some onion cells. JPEG compression calculates the Fourier transform of an image and stores it as a series of sine-wave striped patterns. If one arranges tiles of these striped patterns according to stripe frequency and orientation, then shades each tile according to that pattern’s contribution to the final image, one gets a speckle pattern with a bright point in the center. This closely resembles the diffraction pattern created by shining a laser through those onion cells.

For the original experiment that generated these patterns, check out [xoreaxeax]’s original ptychographical microscope. Going in the opposite direction, researchers have also used physical structures to calculate Fourier transforms.

Continue reading “Why Diffraction Gratings Create Fourier Transforms”