As the chip shortage hit, a lot of the familiar ATtiny chips have become unavailable and overpriced, and it mostly stayed the same since then. If you ever searched for “ATtiny” on your favourite electronics component retailer website, however, you’d notice that there’s quite a few ATtiny chips in stock most of the time – just that they’re from a much newer generation than we commonly see, with incompatible pinouts, slightly different architecture and longer model numbers like 412 and 3227. [David Johnson-Davies] from [technoblogy] is here to clarify things, and provide a summary of what the new ATtiny generations have to offer.

In 2019, he posted about 0- and 1-series ATtiny chips, comparing them to the ATtiny series we knew, decyphering the part numbering scheme for us, and providing a comparison table. Now, he’s returned to tell us about the 2- series ATtiny chips, merging the comparison tables together so that you can quickly evaluate available parts by their ROM/RAM size and the SMD package used. He also describes which peripherals are available on which series, as well as nuances in peripheral operation between the three generations. In the end, he reminds us of a simple way to program all these new parts – as it stands, you only need a USB-UART adapter and a 4.7K resistor.

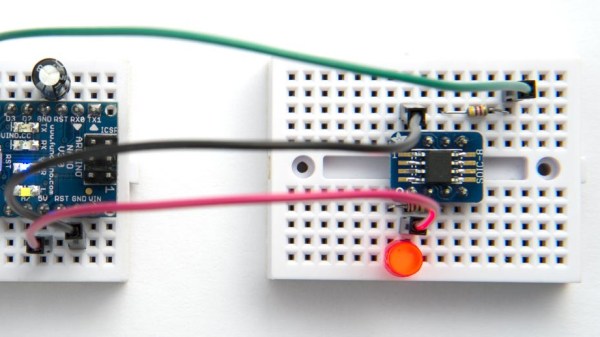

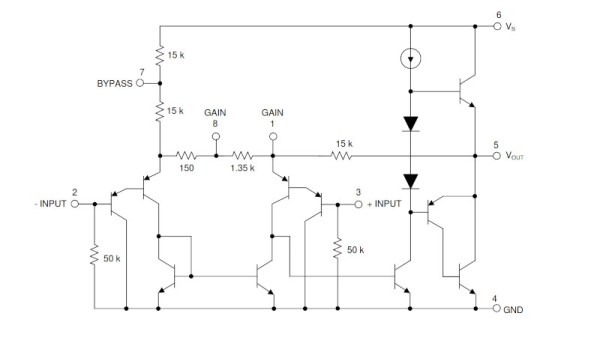

Over the last decades, we’ve seen plenty of inspiring ATtiny projects – squeezing out everything we could out of 5 GPIOs, or slightly more for larger-package ATtiny chips. [David] has been setting an example for us, bringing projects like this function generator, this continuity tester, or an IR receiver with an OLED screen for diagnostics – all with an ATtiny85. It’s not the just pin count that’s a constraint, but the RAM and flash amounts as well – nevertheless, people have fit machine learning and an entire graphics stack into these chips before. If you’re stuck at home unable to do anything, like many of us were during lockdowns, you can always breadboard an ATtiny and see just how much you can get done with it.