Yule Log broadcasts are a bit of an American tradition, though similar content has also been broadcast around the world. They consist of a video of a log burning in a fireplace, ideally merrily so, and often feature Christmas carols or other holiday songs to help create a festive mood. [Joshua Gross] wanted to bring that tradition up to date, and thus built a Yule Log website with the help of some creative technologists.

WebYuleLog.com, as the project is known, features several web-based recreations of the Yule Log concept. They are charming little creations built with different techniques, from the AI-generated to those hewn from simple, pure HTML and CSS. They range from cute 8-bit-esque tributes to burning firewood, to the ethereal and unrecognizable thought bubbles of an image-generating neural network. We’re pretty sure one of them is a oblique reference to an old Excel 97 Easter Egg, too.

It’s funny how much can be achieved within a modern browser window. Once upon a time, you were lucky to get a few GIFs and an obnoxious looping MIDI soundtrack.

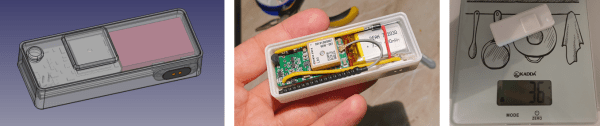

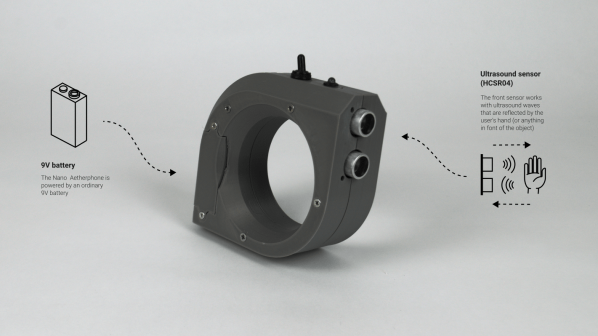

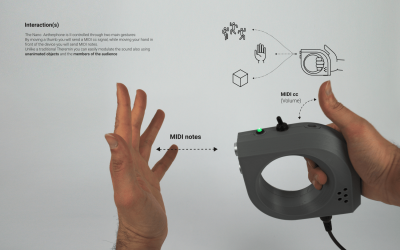

The device is inspired by the Theremin, and was built to celebrate its 100th anniversary. The Nanoaetherphone II is all about using sensors to capture data from wireless hand-wavey interactions, and turn it into MIDI messages. To this end, it has an LDR sensor for detecting light levels, which determines volume levels. This is actuated by the user’s thumb, blocking the sensor or allowing ambient light to reach it. At the front of the handheld unit, there is also an ultrasonic range sensor. Depending on how close the sensor is to the user’s hand or other object determines the exact note sent by the device. As a MIDI controller, it is intended to be hooked up to an external synthesizer to actually generate sound.

The device is inspired by the Theremin, and was built to celebrate its 100th anniversary. The Nanoaetherphone II is all about using sensors to capture data from wireless hand-wavey interactions, and turn it into MIDI messages. To this end, it has an LDR sensor for detecting light levels, which determines volume levels. This is actuated by the user’s thumb, blocking the sensor or allowing ambient light to reach it. At the front of the handheld unit, there is also an ultrasonic range sensor. Depending on how close the sensor is to the user’s hand or other object determines the exact note sent by the device. As a MIDI controller, it is intended to be hooked up to an external synthesizer to actually generate sound.