We just got home from Supercon and well, it was super. It was great to see everyone, and meet a whole bunch of new folks to boot! The talks were great, and you can see a good half of them already on the Hackaday YouTube channel, so for that you didn’t even have to be there.

The badge hacks were, as with most years, out of this world. I’ll admit that my cheeks were sore from laughing so much after emceeing it this year, due in no small part to two hilarious AI projects, both of which were also righteous hacks in addition to full-on comedy routines. A group of six programmers got all of their hacks working together, and the I2C-to-MQTT bridge had badges blinking in sync even in the audience. You want blinkies? We had blinkies.

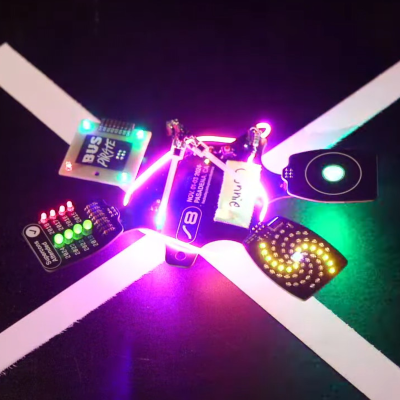

But the hack that warmed everyones’ hearts was “I figured it out” by [Connie]. Before this weekend, she had never coded MicroPython and didn’t know anything about I2C. But yet by Sunday afternoon, she made a sweet spiral animation on the LED wheel, and blinked the RGBs in the touchwheel.

But the hack that warmed everyones’ hearts was “I figured it out” by [Connie]. Before this weekend, she had never coded MicroPython and didn’t know anything about I2C. But yet by Sunday afternoon, she made a sweet spiral animation on the LED wheel, and blinked the RGBs in the touchwheel.

What I love about the Hackaday audience is that, when the chips are down, someone doing something new for the first time is valued as much as some of the more showy work done by more experienced programmers. Hacking is also about learning and pushing out boundaries after all. The shouts for “I figured it out” were louder than any others in the graphics hacks category, it took home a prize, and I was smiling from ear to ear.

Hackaday can learn from this too. [Connie]’s hack definitely shows the need for another badge-hack category, first timers, because we absolutely should recognize first tries. There was also a strong petition / protest from people who had worked new hacks onto previous year’s badges – like [Andy] and [koppanyh]’s addition of bit-banged I2C to the Voja 4 badge from two years ago, and [Instant Arcade]’s Polar Pacman, which he named “Ineligible for this Competition” in protest. Touche.

We’re stoked to learn new things, see new hacks, and basically just catch up with everything folks did over the weekend. We can’t wait to see what you’re up to next year!

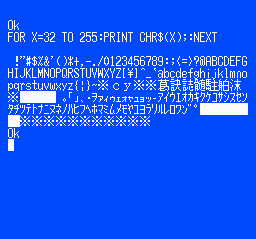

removable cartridge, complete with a BASIC interpreter and a collection of graphical editor tools for game creation.

removable cartridge, complete with a BASIC interpreter and a collection of graphical editor tools for game creation. even a map editor. We think inputting BASIC code via a gamepad would get old fast, but it would work a little better for graphical editing.

even a map editor. We think inputting BASIC code via a gamepad would get old fast, but it would work a little better for graphical editing.