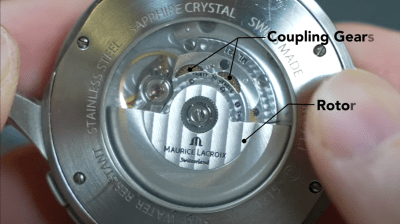

The internal mechanisms that are used in timepieces have always been fascinating to watch, and are often works of art in their own right. You don’t have to live in the Watch Valley in Switzerland to appreciate this art form. The mechanism highlighted here (from Mechanistic on YouTube) is a two-way to one-way geared coupler (video, embedded below) which can be found at the drive spring winding end of a typical mechanical wristwatch. It is often attached to a heavily eccentrically mounted mass which drives the input gear in either direction, depending upon the motion of the wearer. Just a little regular movement is all that is needed to keep the spring nicely wound, so no forgetting to wind it in the morning hustle!

The idea is beautifully simple; A small sized input gear is driven by the mass, or winder, which drives a larger gear, the centre of which has a one-way clutch, which transmits the torque onwards to the output gear. The input side of the clutch also drives an identical unit, which picks up rotations in the opposite direct, and also drives the same larger output gear. So simple, and watching this super-sized device in operation really gives you an appreciation of how elegant such mechanisms are. Could it be useful in other applications? How about converting wind power to mechanically pump water in remote locations? Let us know your thoughts in the comments down below!

the centre of which has a one-way clutch, which transmits the torque onwards to the output gear. The input side of the clutch also drives an identical unit, which picks up rotations in the opposite direct, and also drives the same larger output gear. So simple, and watching this super-sized device in operation really gives you an appreciation of how elegant such mechanisms are. Could it be useful in other applications? How about converting wind power to mechanically pump water in remote locations? Let us know your thoughts in the comments down below!

If you want to play with this yourselves, the source is downloadable from cults3d. Do check out some of the author’s other work!

We do like these super-sized mechanism demonstrators around here, like this 3D printed tourbillon, and here’s a little thing about the escapement mechanism that enables all this timekeeping with any accuracy.