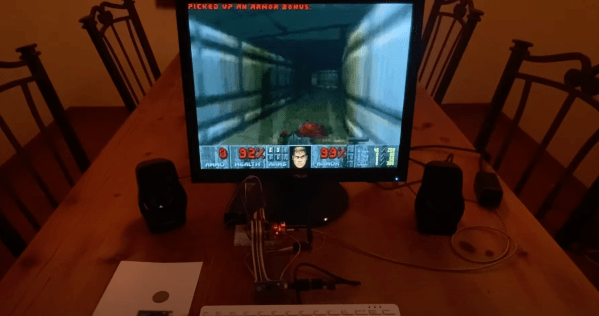

To the point of being a joke, it seems like DOOM is adapted to run on everything these days. So it was only natural that we would see it ported to the RP2040 by [Graham Sanderson], the tiny chip powering the Raspberry Pi Pico.

You might be thinking, what’s different about this port? There have been 55 articles about DOOM here on Hackaday, showing it running on everything from web checkboxes to desk phones. The RP2040 has 256 K of RAM, two decently clocked processor cores, and 2 MB of flash, so it’s not the most constrained platform ever to have DOOM run it. But [Graham] also set some very lofty goals: all nine levels needed to be playable, faithful graphics and music, multiplayer, and it would output to VGA directly. It should play just like the original. DOOM has a demo that is stored as a sequence of input events. They form excellent regression tests as if the character gets stuck or doesn’t make it to the end; then you’re not accurate according to the original code.

There are two big problems right out the gate. First, a single level is larger than the 2 MB storage that the RP2040 has. And to drive the 320×200 display, you either need to spend a lot of your CPU budget racing the beam or allocate a vast amount of RAM to framebuffers, making level decompression much harder.

A default compression scheme wouldn’t cut it because it needed a high compression ratio and random access since decompressing into RAM wasn’t an option. However, carefully optimizing and compressing the different data structures yielded great results. Save game files are given a similar treatment to ensure they fit into the remaining flash after all the levels (34k).

The result is fantastic, and it supports DOOM, Ultimate DOOM, and DOOM II. The write-up goes into far more detail than we could here; enjoy the read. If you decide to make a day trip to the depths of Hell on your own Pi Pico, be sure to let us know in the comments.

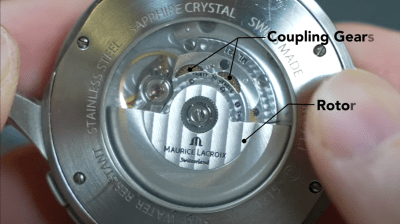

the centre of which has a one-way clutch, which transmits the torque onwards to the output gear. The input side of the clutch also drives an identical unit, which picks up rotations in the opposite direct, and also drives the same larger output gear. So simple, and watching this super-sized device in operation really gives you an appreciation of how elegant such mechanisms are. Could it be useful in other applications? How about converting wind power to mechanically pump water in remote locations? Let us know your thoughts in the comments down below!

the centre of which has a one-way clutch, which transmits the torque onwards to the output gear. The input side of the clutch also drives an identical unit, which picks up rotations in the opposite direct, and also drives the same larger output gear. So simple, and watching this super-sized device in operation really gives you an appreciation of how elegant such mechanisms are. Could it be useful in other applications? How about converting wind power to mechanically pump water in remote locations? Let us know your thoughts in the comments down below!