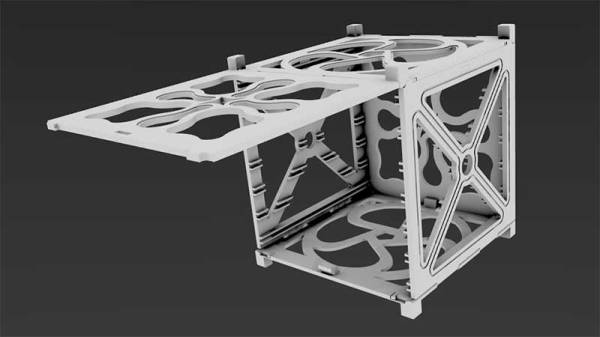

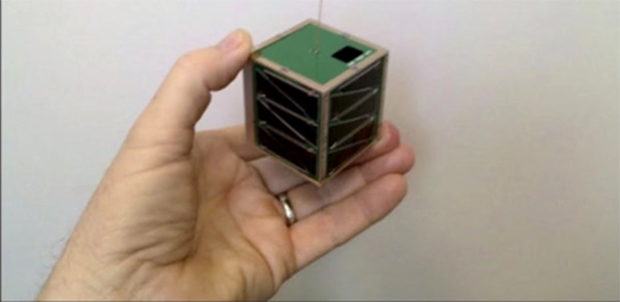

CubeSats are tiny satellites which tag along as secondary payloads during launches. They have to weigh in at under 1.33 kg, and are often built at low cost. There’s even open source designs for these little spacecrafts. Over 800 CubeSats have been launched over the last few years, with many more launches scheduled in the near future.

[Thomas Cholakov] coupled a homemade cloverleaf antenna to a software-defined radio to track some of these satellites. The antenna is built out of copper-clad wire cut to the correct length to receive 437 MHz signals. Four loops are connected together and terminated to an RF connector.

This homebrew antenna is connected into a RTL-SDR dongle. The dongle picks up the beacon signals sent by the satellites and provides the data to a PC. Due to the motion of the satellites, their beacons can be easily identified by the Doppler shift of the frequency.

[Thomas] uses SDR Console to receive data from the satellites. While the demo only shows basic receiving, much more information on decoding these satellites can be found on the SDR Satellites website.

This looks like a fun weekend project, and probably the cheapest aerospace related project possible. After the break, watch the full video explaining how to build and set up the antenna and dongle.