As circuits find their way into more and more real-world environments, the old standard circuitry isn’t always up to the task. It wasn’t that long ago that a computer needed special power, cooling, and a large room. Now those computers wouldn’t cut it for the top-of-the-line smartphone. However, most modern circuits don’t bend well and don’t like getting wet.

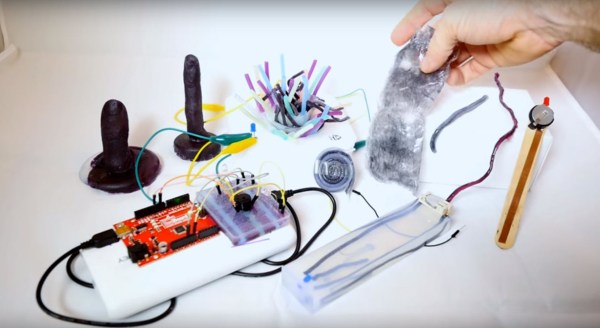

An international team of researchers is developing chemical-based circuitry that uses gold nanoparticles and electrically charged organic molecules to build circuit elements that behave like semiconductor diode junctions. It’s simple to make flexible circuits that don’t mind being wet using this chemical soup.

In an interview with IEEE Spectrum, the developers mentioned that other circuit elements similar to transistors and light sensors should be possible. The circuits aren’t perfect, however. The switching speed needs improvement. Also, while conventional circuits don’t like to get wet, these chemical circuits have difficulties if things get dry. Still, like all technology, things will probably improve over time.

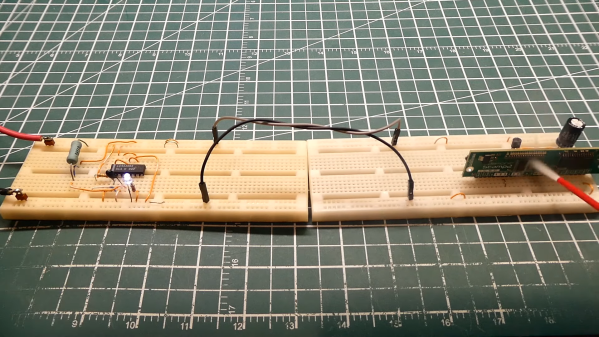

This technology needs a good bit of engineering refinement before it is practical. If you need flexible photosensitive circuits in the near term, you might try here. Meanwhile, waterproof circuitry just needs the right kind of enclosure.

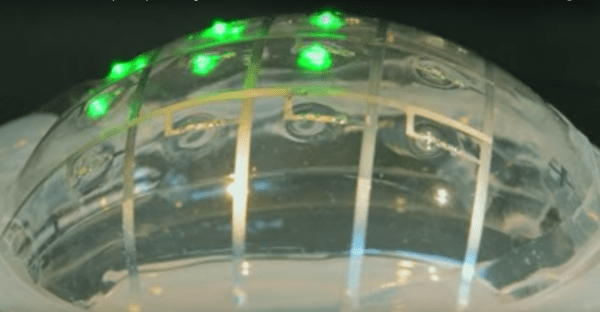

Photo Credit: UNIST/Nature Nanotechnology

Researchers at the

Researchers at the